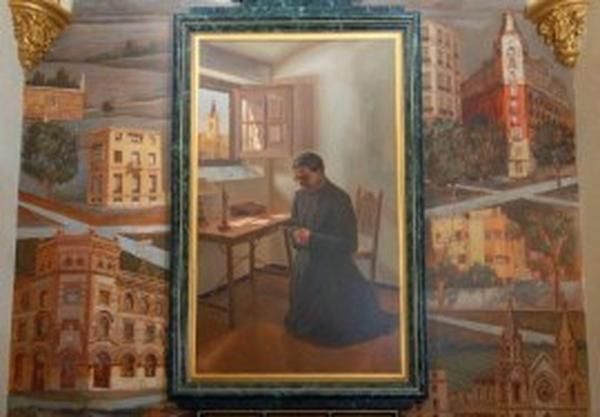

In 1931, the founder of Opus Dei wrote down what had transpired during the morning of October 2nd 1928 while attending a retreat on Garcia de Paredes Street in Madrid: “I received an illumination about the entire Work, while I was reading those papers. Deeply moved, I knelt down (I was alone in my room, between talks) and I gave thanks to our Lord. I remember with a heart full of emotion the ringing of the bells of the church of Our Lady of the Angels... I put the loose notes I had been taking up till then into some sort of order.”[1]

The light St. Josemaría received that day was an entrance by God into history. God continues acting in the world, in the hic et nunc, in the here and now of the life of men and women. The Work is Opus Dei, operatio Dei. “God is working” insisted Pope Benedict XVI during his trip to France, citing the Gospel of St. John. “Thus human work was now seen as a special form of human resemblance to God, as a way in which man can and may share in God’s activity as creator of the world.”[2] God will always continue working in his Church, transforming the world and converting souls. As we read in the fourth Eucharistic Prayer, the Holy Spirit was sent from the Father through the Son to bring his work to completion in the world: opus suum in mundo perficiens.

I received an illumination about the entire Work. The whole of Opus Dei was already present on October 2, 1928, although the light received on February 14, 1930, would make the founder understand that women were also to form part of the Work. While the juridical solution for the priests would not come until February 14, 1943, on October 2nd the priesthood was already present: St. Josemaría was the first priest of Opus Dei. The Work was born in the Church, and God chose a priest to found it. Opus Dei was to proclaim the universal call to sanctity and apostolate, the sanctifying value of professional work done as well as possible, when it is transformed into prayer and service to others.

"Human work was now seen as a special form of human resemblance to God, as a way in which man can and may share in God’s activity as creator of the world."

Deeply moved, I knelt down. St. Josemaria’s reaction reflects his faith. To kneel is to recognize that one is facing a Mystery: a reality that is sacred and, therefore, that does not belong to us. If this exterior act is accompanied by an authentic interior attitude, it manifests both faith and humility. Everything comes from God. He counts, certainly, on our generous response, but it is He who has chosen us and loved us first. Faced with God’s goodness, the founder’s heart spontaneously poured forth an act of thanksgiving: I gave thanks to our Lord.

In the New Testament, the act of kneeling or of prostrating oneself signifies obedience, respect. This is how the leper acted when he met Christ, and the disciples in the boat, after Jesus calmed the storm. In the darkness of Gethsemane, our Lord, kneeling on the hard rock, spoke a loving “yes” to the Will of the Father. Jesus kneels from the humility of his human will, united to his divine will, with a physical gesture whose symbolism remains valid for all times and cultures. As Cardinal Ratzinger pointed out, in the early Church the devil was portrayed without knees, because he lacks the power of God: he doesn’t know how to love. “The inability to kneel is seen as the very essence of the diabolical.”[3]

In contrast to the fallen angel, the myriad of angels in heaven sing the glories of God. On October 2, 1928, the bells of the church of Our Lady of the Angels were perhaps calling the people to gather for Mass, or simply marking the hours. The pealing of those bells resounded in St. Josemaria’s heart during his whole life. It was in his heart, on the feast of the Holy Guardian Angels, that the seed of the Work was born.

With the vision of faith, after the light he received on October 2nd, the founder saw the Work projected in time and space. What did he see? Above all, the people, one by one, many souls, “men and women of God who would raise up the Cross with the teachings of Christ at the summit of all human activities.”[4]

Transmitting the seed of Opus Dei is, above all, drawing souls to God, to Jesus Christ. “Anyone who does not realize that he is a child of God is unaware of the deepest truth about himself. When he acts he lacks the dominion and self‑mastery we find in those who love our Lord above all else.”[5]

A child of God loves the world born good from God’s hands and all men and women. Human work is born of love; wisdom is the science of love; sanctifying work is an art, a path to God. It is a passionate collaboration with God, which gives meaning to life, and therefore sureness and security because God never abandons us. Each of us has to be a teacher of holiness, even with our miseries, and transmit the faith with a dedication that allows the soft breeze of the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Christ, to act.

The center of salvation history is Jesus Christ, true God and true man. We are his people who, convoked in the Eucharist, become the Body of Christ. In the Mass, the Church offers Christ, and offers herself, and thus becomes the Church: the Body of Christ.

The same is true of the Work, a small “portion” of the Church, as St. Josemaria liked to say. The spirit of the Work spurs us to “serve the Church, and all men, without using the Church.”[6] Every Christian carries with them, so to speak, the whole Church, the heavenly hosts, and the saints. All the saints, each one of them, are ours, from the good thief to St. Narcisa, the Ecuadorian woman canonized by Benedict XVI in October 2008.

On October 2, 1928, when St. Josemaria “saw” the Work, he had just finished celebrating Holy Mass, for the salvation of the world. Through the penitential rite and many other prayers from the Canon, he had shown, with all the passion of a good priest seeking God’s will, his desire to have a clean heart. He did not yet know that he was to be a herald of the sanctification of ordinary life, who would remind so many people of the need to offer God spiritual sacrifices of a pleasing aroma, united to the Sacrifice of the Mass, the center and root of the interior life. The mystery of the passion, death, resurrection and ascension of Christ, seated at the right hand of the Father, had been made present.

"Each of us has to be a teacher of holiness, even with our miseries, and transmit the faith with a dedication that allows the soft breeze of the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Christ, to act."

In the actualization of the paschal mystery, Christ offers himself under the appearances of bread and wine, fruit of the earth, of the vine, and of the work of man. The bread is no longer bread, it is his Body; the wine is his Blood. Jesus is really and substantially present, with his Body, his Blood, his Soul and his Divinity. Ecce Agnus Dei, ecce qui tollit peccata mundi. Heaven has come down to earth, and the celestial liturgy is anticipated, the supper of the marriage feast of the Lamb, as the ordinary form of the Latin Rite emphasizes: Beati qui ad cenam agni vocati sunt. St. Josemaría would also have read those words now found in the Missal of Blessed John XXIII: Corpus tuum, Domine, quod sumpsi, et Sanguis, quem potavi, adhaereat visceribus meis. The Body and Blood of Christ filled the soul of that twenty-six-year-old priest, who was about to “see” Opus Dei.

On October 2, St. Josemaria gave thanks to God and began to work. I put the loose notes I had been taking up till then into some sort of order. Although he later thought, in his humility, that he had been slow to follow the divine inspiration, St. Josemaría worked a lot and well. Opus Dei was thus the fruit of divine initiative and human correspondence, a manifestation of the Holy Spirit guiding and sanctifying his people. As the Second Vatican Council would insist,[7] God wanted his Church to have a renewed awareness of the universal call to sanctity, with faithful in the Church committed to sanctifying the world from within, spreading this message with their lives.

The liturgical feast of the Holy Guardian Angels began to be celebrated in Spain and France in the fifth century. In 1670, Pope Clement X extended it to the universal Church, celebrated on the 2nd of October. The fact that God wanted the founder to see the Work on the feast of the Holy Angels is, for us, a call by Providence to never lose our supernatural viewpoint. There are many angels on our path; they guard us obeying God’s commands and always blessing him, as Scripture recalls in texts that, in 1928, were read in the liturgy of the Mass for October 2nd.[8]

Our acts of thanksgiving are directed to the Virgin Mary, the first opus Dei by reason of excellence, as St. John Paul II said during an audience granted in the first days of his pontificate to Blessed Alvaro del Portillo. Let us ask our heavenly Mother to make us small, humble, so we may be filled with God.

Guillame Derville

Footnotes:

1. A. Vazquez de Prada, The Founder of Opus Dei , vol 1, Scepter 2001, p. 220.

2. Pope Benedict XVI, Encounter with the World of Culture in the College des Bernardines in Paris, 12 September 2008; cf. Jn 5:17.

3. Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, Part 4, ch. 2, p. 193.

4. A. Vazquez de Prada, The Founder of Opus Dei , vol 1, Scepter 2001, p. 288.

5. St. Josemaria, Friends of God, no. 26.

6. St. Josemaria, Conversations , no. 47.

7. Cf. Lumen Gentium no. 11.

8. Cf. Ex 23:20-23; Ps 91[90]:11-12; 103[102]:20-21.

![]() St. Josemaria speaks about the founding of Opus Dei in this brief video.

St. Josemaria speaks about the founding of Opus Dei in this brief video.