August 30, 1936. For a bit more than a month Spain has been split into two factions, increasingly squaring off in a fratricidal war. The life of Father Josemaría, like that of so many other priests, is at risk. He moves from one hiding place to another. Militiamen hang a man who looks like him, right in front of his mother’s house, thinking that it was he. Now he is in the home of some friends, together with Juan — one of the first members of the Work — and a young man he met only two days previously. About two in the afternoon, a group of soldiers, sweeping the neighborhood in an intense manhunt for enemies, rings the bell. Catholics, especially priests and religious, are prime targets. The voice of the elderly maid answering the door is loud enough to be heard all over the house:

“Oh! You must be here for the search and requisition… The owner isn’t here, but make yourselves at home!

The three guests scamper up the service stairway and take refuge in an attic. The space is narrow, low-ceilinged, soot-filled, without ventilation. They crouch behind some old furniture. Time drags on silently and interminably. The heat becomes unbearable. Now they hear the soldiers approaching. At the end of the methodical search they arrive at the top floor and enter the room next door. The Father whispers to the two youths:

“We’re in a tight spot. If you wish, make an act of contrition while I give the absolution.”

He absolves them. Juan asks him,

“Father, and if they kill us, what will happen?”

“Why, we’ll go right to heaven, my son.”

Juan finds the thought so comforting that he falls asleep. The other two hear meticulous rummaging in the next room. Now it’s time for their hiding place…

But no. Instead the soldiers descend the stairway and vanish. The fugitives heave a sigh of relief, but stay put until nine in the evening, until after the main gate to the patio of the apartment building is closed. They are sweaty, dehydrated, dirty. One of the youths goes down to one of the apartments:

“Please, could you give me a glass of water?”

The maid, startled, allows him to enter.

“Upstairs there are two more persons.”

“Well then, tell them to come down right now!”

They are able to wash up and change clothes. The Father smiles, drawing a moral from the incident:

“Until today I never knew the value of a glass of water!”

They gladly accept the hospitality offered by the woman. The next day the soldiers continue to scour the building. Frequently they knock on the door for help with one thing or another; each time she trembles with fear. She suggests saying the rosary, and the Father takes her up on it, not hiding his identity:

“I’ll lead it. I’m a priest.”

A day later he thanks his hosts, but tells them that he is leaving immediately in order not to be a danger for them or compromise their situation.Once again a desperate search for yet another place of refuge, none really safer than the last.

With the outbreak of the war, the few members of Opus Dei were forced to scatter. The Father — as he had come to be called familiarly by his spiritual sons — moved from one shelter to another, always in danger. With heroic fortitude he declined a few secure hiding places that were unsuited to his priestly condition. At times the safest place was the street, where he walked from morning until night blending into the crowd.

Hard times, apostolate and cheerfulness

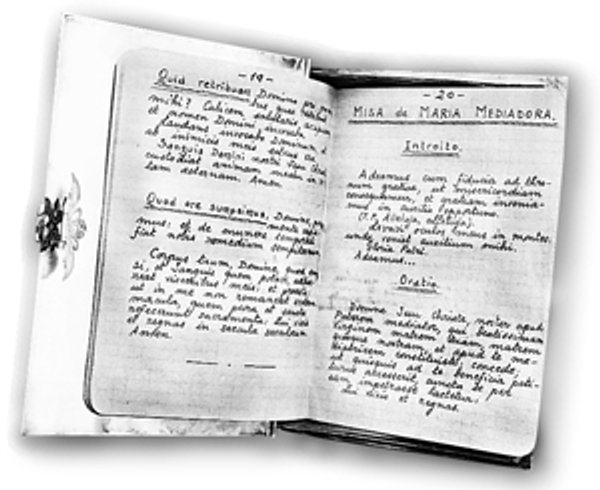

In the midst of this he continued to celebrate Mass when possible and to provide priestly assistance to many, besides the members of the Work, whom he was able to contact. He even preached a retreat by setting up a series of appointments in unlikely places. News arrived of martyred priests, friends of his.

For a number of months he found temporary haven in a psychiatric clinic, feigning madness with the complicity of its director, Dr. Suils. At last he was able to obtain entrance for himself and several companions at the consulate of Honduras. Its diplomatic status guaranteed a modicum of safety. Sites such as this one were packed with refugees, food was scarce, the atmosphere depressed and tense. Father Josemaría drew up a schedule for his young followers, had them devote time to study, preached to them, and even discreetly reserved the Blessed Sacrament in a small desk. His great joy was being able to celebrate Mass every day. The engineer Isidoro Zorzano, who could move about freely because of his Argentine citizenship, served as a means of contacting those outside the consulate.

But how long would this war go on? When would the persecution end? How long could he be stuck in this situation, without being able to begin the expansion of the Work? He thought it over and consulted with the young men who followed him. Yes, it was necessary to cross over to the other part of Spain where a normal Christian life was possible. The only practical way, although it held no guarantee of success, was to cross the Pyrenees and get there by way of France. It was September 1937.

Crossing the Pyrenees

It would have been very easy for anyone in his place to ask himself why so many difficulties were arising to block a project that was clearly divine. Why did God permit such obstacles? But the young priest, who from the time of his childhood had learned to swallow the bitterness of deep sorrow, was already an expert in the science of the Cross. It was not resignation, but deep understanding of the path of suffering, since it was on the cross that Christ triumphed and saved us. He was convinced of this all his life. Thus he wrote, referring to himself, “When you celebrated the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross you asked our Lord, with the most earnest desire of your heart, to grant you his grace so as to ‘exalt’ the Holy Cross in the powers of your soul and in your senses. You asked for a new life; for the Cross to set a seal on it, to confirm the truth of your mission; for the whole of your being to rest on the Cross!”

Yet it was not an easy decision for the founder. The idea of leaving some of his people and his mother with his brother and sister behind in war-time Madrid tormented him. Nevertheless he realized the urgency of carrying on with the apostolate that he knew to be the will of God. And for better or worse, on the other side of the battle front he could do that.

With improvised documentation he arrived in Barcelona on October 10, 1937. This was the city from which “convoys” of refugees departed, guided by mountaineers and smugglers — all undercover, as the circumstances required. He and those with him had to wait for about a month, hungry and with almost no spending money, until a convoy could be organized.

Crossing the mountains by foot, in late-autumn chill, walking by night and hiding by day, without equipment of any type, with the physical weakness resulting from months of deprivation, in constant danger of being discovered and shot… this was a tall order for anyone, especially for persons already tested by a war both too long and inhumane. The stages of the escape were numerous and rough. At times, they waited for days in some outpost, at the guide’s orders. Father Josemaría introduced himself as a priest right away and celebrated Mass whenever possible. The last of these Masses, in the shelter of a grotto, kneeling for the whole celebration before an altar of rock, moved the entire group: “Never have I heard a Mass like the one today. I don’t know if it is due to the circumstances or because the priest is a saint,” wrote one of those present.

On December 2, good fortune allowed them to cross the border of Andorra. They were exhausted but safe. A heavy snowstorm stranded them in Andorra for several days. But at last they could resume the journey through France, with a stop at Lourdes to thank our Lady. When they crossed back into Spain at Hendaye, Father Josemaría recited a Hail Holy Queen.