Biography of Pedro Ballester by Fr George Boronat in Amazon

Five years have passed since the death of Pedro Ballester. Now with a bit more perspective, what was Pedro’s secret to being happy despite his illness?

On one occasion Pedro felt nauseated by the treatment he was receiving at the time and vomited in his hospital room. A nurse was immediately called to lend a hand. When the nurse arrived, Pedro who was still bent over and feeling very sick, recognized her and asked her about her family and about a matter for which she had asked Pedro to pray. There are thousands of stories from Pedro’s life that illustrate this, but I think everyone remembers going to visit Pedro and ending up talking about themselves and not about Pedro. In the hardest moments, his generosity continued to be the cause of his joy. Although at times it was more difficult for him to smile. I think one of the most striking features of his personality was that he lived outwards. Since childhood he was very sensitive to the needs of others. Saint Josemaría taught: “Sincerely giving yourself to others is so effective that God rewards you with a humility full of joy” (Forge, 591). Joy is the fruit of dedication to others.

The law of the Church indicates that at least five years must pass since the death. When do you intend to initiate the Cause? Has the devotion to Pedro spread enough to start the process?

The bishop of the city where Pedro died is the one who must first decide if there are sufficient reasons to start the Cause of Canonization. At the moment, numerous requests have arrived (including some from bishops and a cardinal) to study this possibility. The devotion spread like wildfire from the very beginning. Before Pedro died, there were already thousands of people who prayed for him and hundreds who had known him and were aware of the depth of his interior life. There were also dozens who were able to be with him in the last days and who saw the way he died. Shortly after his death, an English bishop had already composed his own prayer for private devotion, and permission was soon obtained from the Manchester local bishop to print it. Almost immediately people from different countries began translating it into their own languages, so now it is available in fourteen languages. It all happened very fast.

The Synod on Young People, which was held in 2018, proposed a list of Young Witnesses as models for today’s youth: Montse Grases, Carlo Acutis, Gianluca Firetti or Chiara Badano, among others: do you think Pedro could be one of them?

He already is! Pedro already inspires many young people. To those who knew him before he died and to those who are now discivering his story. But Pedro’s case is perhaps distinctive because he had a very normal life and was in contact with many people. His intense apostolate was carried out with non-practising Catholics, with non-Catholics and with many non-believers. In a secular society like that of the United Kingdom, Pedro dialogued and made friends with all kinds of people from very varied social situations. Those who knew him always highlight his naturalness. Pedro was very normal, very human, very close. And so he has become a very accessible model. A normal boy who goes to a normal school, who goes to university like other people, a fan of video games, with a mobile phone, WhatsApp or Spotify. Someone with the same struggles to practise holy purity, temperance, detachment from material things. Someone who tries to bring his friends closer to God in a paganized and secularized environment. Someone who has had to overcome the same attacks on Christian freedom or the impositions of corrosive ideologies, who sometimes finds it difficult to pray, read the Gospel, not get distracted during the rosary, etc.

Both the book and the documentary feature many friends. It is striking that his classmates from Imperial College, with whom he had shared a classroom for only three months, travel to Manchester to visit him when he is diagnosed with bone cancer. What made Pedro have so many friends?

As I have pointed out before, Pedro lived outwards. His interest in others was genuine. His affection was real and his generosity was magnetic. It transcended differences of nationality, religion, social or cultural stratum. Many are not used to meeting people for whom friendship is not a means, but an end. Whoever came into contact with Pedro was struck by his affection for everyone.

Perhaps some people his age will be surprised by Pedro’s eagerness to learn about matters that had nothing to do with chemical engineering. It is striking that he was passionate about international politics, history, etc. How did he have that open-mindedness?

The UK is a crossroads of social and cultural currents. It is very common to attend class with people of many different nationalities, cultures and religions. Living amid such diversity it is natural that in conversation with others one’s sights are opened. In the Catholic environment it is very common to live with Catholics who are fleeing persecution in their countries of origin. Pedro was friends with Nigerian, Chinese, Syrian, Indian, Pakistani Catholic families... All world conflicts end up generating a flow of refugees to the United Kingdom. Pedro asked a lot and learned a lot about these conflicts and especially about religious persecution in different countries.

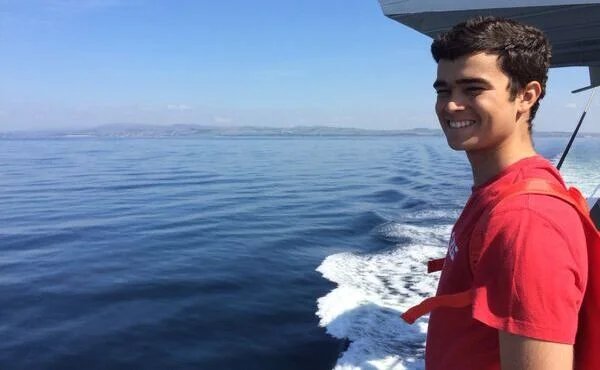

Documentary on Pedro Ballester

In some of the statements in the documentary, both his brother Carlos and his friend Lawrie agree that sometimes Pedro was very insistent, too pragmatic, or that when he saw something clear he did not compromise. How did he fight against his defects?

His struggle can be glimpsed in his personal notes. Every week he went to spiritual direction with the intention of improving, of changing. He took notes of his resolutions and reviewed them every night in the examination of conscience. He was aware of his shortcomings and sometimes suffered because of them. For example, with his impatience with some Greygarth resident who didn’t study because he didn’t want to, and who stayed playing on the computer instead of going to class or who didn’t feel like helping anyone at all. Fighting against the anger, he tried to pray for them and then he thought how he could help them. Towards the end of his illness, the laughter of others annoyed him, but he realized that it was his problem, due to his circumstances, and he prayed to be able to die with joy.

A particular moment in his illness was when he asked to see Pope Francis, and how he was able to tell him that he offered his pains to God for the Church and for the Holy Father.

Pedro expressed his desire to see Pope Francis. Mgr Carlos Nannei passed the message on and the Pope told him that he would be delighted to receive him. It was a relaxed and cordial meeting. Pedro gave him a card signed by the patients, doctors and nurses of Christie Hospital’s adolescent cancer ward where he was being treated, and the Pope blessed it. The Pope listened to him and looked at him with great affection. At the end he blessed him. The family gave him a very old picture of Saint Joseph, from Seville, and a jar with “dulce de leche” because his mother knew that the Pope liked it. He laughed heartily when he saw it and said to Pedro: “It’s just that mothers know everything!” Upon returning to Manchester, in the hospital they put the photo of Pedro with the Pope in the music room in the teenage cancer area.

It is striking that, not only in his childhood but also in his adolescence, he had a wonderful relationship with his parents and with his two brothers. What would you highlight about the Ballester family?

The family is essential in the formation of character. His parents taught him to pray and prayed with him. They attended Mass as a family and the three brothers were altar boys in the parish. They prayed the rosary as a family each day. It is at home that one learns to be holy. There he learned to be generous, to be responsible. As his brother Carlos explains, Pedro was always an older brother. The three brothers were born in a period of three years. That short age difference helped them to be very close. They were (and are) very good friends. They played together, they often went out together and they enjoyed being with each other.

The UK is home to people of many religious faiths, agnostics and atheists. And the number of Catholics and Opus Dei people is not very high. Pedro dreamed of spreading the Christian message of Opus Dei at his university and throughout the country. Cardinal Roche says that wonderful things have begun to happen. Can you tell us about any?

Indeed, Catholics are a minority and Opus Dei is not well known in general in the UK. Many times, at school or when starting at university, people come into contact with people of faith for the first time. It is a very respectful environment and very interesting, where open and genuinely cordial conversations can be had. There are, of course, certain prejudices sometimes, held by misinformed people. But very rarely animosity. Rather, curiosity. In these circumstances, evangelizing is as natural as making friends because, after all, they identify with each other. There are constant conversions to the Catholic Church in the UK. Pedro helped several people convert during his life and now continues to arouse interest in many souls. All the conversions that I have witnessed are the result of the example of the Catholic faithful, rather than of doctrinal discoveries. The testimony of Pedro’s life is, in this sense, a great trigger for conversions.

In December 2014, he was diagnosed with osteosarcoma. After one treatment, they took him to Germany to receive another, experimental one, which gave good results. Until in February 2017 the cancer returned with force and they told him that he had 12 months to live. He is barely 20 years old and, at that moment, he makes an effort to smile so that his mother does not cry.

Osteosarcoma in young people is a very aggressive cancer. During the first two years Pedro received different treatments and his worst moments occurred as a side effect of the chemotherapy cycles. Sometimes it seemed that the tumor was inactive. Also, there was an army of people praying for him and Pedro had a lot of faith. In a letter he confessed to me that, although he knew he could die, he always thought that he would last much longer. When he was told in February 2017 that resources had been exhausted and that life expectancy would be less than a year, Pedro was taken by surprise. He received the news with his parents. Seeing how it affected them, Pedro smiled to encourage them. Later he would confess that that was a hard blow and that he could only smile because his mother was with him. Then he changed his attitude. In addition to preparing to die, he made it a point to help his family prepare for that moment.

Greygarth Hall is the students’ residence of Opus Dei in Manchester, where Pedro lived. How was Pedro’s illness and death experienced there?

The doctors were very surprised that Pedro wanted to spend his last days in Greygarth, surrounded by students and friends. Nowadays death tends to be hidden. Many die alone in a hospital room. However, Pedro was accompanied day and night by his parents and siblings, friends and other members of Opus Dei. His room was situated in a quiet part of the house where Pedro could receive visitors and rest when needed. All the residents turned to him and spent a lot of time in his room. Some even decided to stay over the Christmas holidays to be with him in his last days. Seeing Pedro die was an event they would never forget. As his uncle said when watching him die: “If I had been offered the option of witnessing an event on this earth, this would be the one I would choose.”

Reading the life of Pedro, might we think that holiness is only for some very special people?

We love to think that those who do special things have something special that we don’t have. So we excuse ourselves. Those who knew him attest that Pedro was very normal. He certainly had talents. He was very intelligent, for example. But one is not born smiling, being generous, kind, attentive to others or devout. No one is born special, but one becomes special. By reading the notes that Pedro took in his prayer or in his examination of conscience, his struggle is understood. From the outside, it would seem that everything came to him spontaneously, that he was like that. But that is not the case. He became like this, with the help of God and many people. For example, his apostolic zeal was striking, it seemed like a natural talent. But when reading his intentions, one sees how he asked in his prayer to be freed from human respect, to overcome shame, or how he made an effort to talk to one or the other without excusing himself thinking that he did not know that person well or that he would not respond well. Holiness is struggle. And reading the struggle of others always helps to understand it better.

Sometimes there is talk of a canonized person looking at an aspect of his life. For example, Saint John Paul II defined the founder of Opus Dei as the saint of the ordinary. How would you define Pedro?

From a young age, Pedro had an apostolic and missionary calling. He knew he was an apostle. Also, he had a genuine love for people and that’s why he attracted them. Perhaps Pedro can be remembered for his apostolic zeal. Bringing souls closer to God was his passion and his mission.