KENYA FIGHTING DISCRIMINATION

(published in The Nigerian Observer, January 1, 2015)

IN 1958 racial tensions were running high in Kenya, a black African nation ruled by whites.

The powder-keg atmosphere was made even more explosive because Africans were split into 40 separate tribes; some, long-standing enemies. A state of emergency was in force, the legacy of the Mau Mau rebellion which began in the early 1950s and took more than 10,000 lives, most of them black Africans; thousands more went to detention camps. In Nairobi most native Africans were servants; few were seen.

In the classrooms of upper secondary schools there were no native Africans. But what the British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, would describe as "the winds of change" were already blowing fiercely in Africa. "We came to Kenya with our project, the first multi-racial school in East Africa, something for all the races and for all religions," recalled Father Joseph Gabiola, Opus Dei's first priest in the country. "We feared the authorities would say: 'What do you mean? This cannot be. Are you mad?'"

The main obstacle was racism. Blocks of land in Nairobi were generally for either Europeans, Africans or Asians. Few could be used for the new college. The land that members of Opus Dei found was in a European residential area and the neighbours objected. "Officially they objected because they did not want a school in the neighbourhood," Father Gabiola said. "But everybody knew the real reason was that the school would have black Africans. There was a meeting in one of the rooms of the local council and we had to go along to answer some questions. There was a huge crowd of whites outside and the thing became quite hot. I don't know why, but the whites were all abusing us. It was in all the newspapers, front page. And in the end they won. We lost the land."

As it turned out losing the first battle was providential. Another block of land was found in Strathmore Road (now Mzima Springs Rd). This time there was no room for complaint—it was adjacent to three European schools.

The goal was to build a boarding school which would bridge the gap between secondary and university. Previously native Kenyans had to leave the country to get a higher education. 'There was a big gap there," Father Gabiola explained. "The aim was to create something to train the students in many areas: academic, human and, for those who wanted it, religious."

After the land problem came financial problems. The first principal, David Sperling, and teacher, Kevin O'Byrne, took the brave step of starting the main building before all the money was raised. The students were all poor so it was useless looking there for help. The colonial government gave some money; some was raised through mortgages but it was not enough; so David Sperling set off for Europe and America in search of benefactors.

When the money problem was under control critics predicted the project would be a disaster anyway. A friend of Father Gabiola, a religious, warned him: "Its going to be a failure because you will not get the students."

"But," Father Gabiola said, "we were determined that, with the grace of God, it would work." David Sperling and Kevin O'Byrne travelled the country looking for students to put their faith in an institution that did not yet exist, and they were successful. "When he heard of it, my friend said: 'Of course you will have Africans, but you will not have Europeans. And Asians, you will not have Asians.' Later I was able to tell him: 'We have found an Asian student.' His reaction was: 'Very good, very good, you will have one.' And then the Europeans wanted to come, through friendship because by this time we had many friends, and so it continued on."

In the early days conditions at Strathmore were primitive. The college was surrounded by bush which ran down into the Nairobi River valley. As students arrived all that could be seen over the maize in front of the new school was the boxes they carried on their heads. The land was infested with cobras. One day a leopard paid a visit, followed by a hyena which chased a student up one of the pillars at the entrance to the main building. More formidable than the physical environment were the racial barriers. These were not restricted to differences between black and white: some tribes had less in common with each other than with the Europeans.

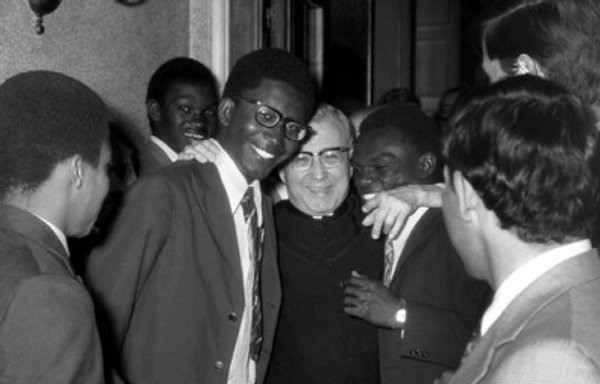

Potential racial tensions were neutralised by Strathmore's family atmosphere, an approach inspired by the words of Opus Dei's founder: "We are brothers, children of the same Father, God. So there is only one colour, the colour of the children of God. And there is only one language, the language which speaks to the heart and to the mind, without the noise of words, making us know God and love one another."

The college shield carried three hearts and the motto was 'ut omnes unum sint," may they all be one. In a homily at the first Mass at Strathmore on a temporary altar, Fr. Gabiola first spoke of Strathmore as a family home. He remembered the surprise on the faces of students: "It was, I believe, a very bold thing to aim at, especially considering the large variety of races, tribes, nationalities and even religions, both among the students and the teachers. It could have been taken as a beautiful thought, as a figure of speech or as an empty dream, but it was taken in earnest, and all responded."

The response was seen in practical things. When one of the first students, Gabriel Mukele, arrived with only one set of clothes, the other students fitted him out with ties, socks and shirts and David Sperling donated his old school suit. Despite these gifts Gabriel felt he was too poor to continue. He decided to drop out and take a job; but David Sperling talked him out of it; he arranged holiday jobs so Gabriel could earn enough to get by.

Integration influenced all aspects of college life. No room was occupied by students of a single race or region. The teachers' rooms were alongside students' rooms. Meals were served at tables of six: a teacher, a European and African students and so on.

One of the early residents, Jacob Kimengich, remembered: "At meal time I found myself sitting at the same table with the principal and, of course, the other teaching staff were also there; and we were eating the same food. This was drastically different from my boarding school days where the food and accommodation was not shared at all. In those days who could think of eating the same food with a Mzungu, let alone sitting at the same table and sharing the same residential building. It was totally unexpected."

Another early student, Wilfred Kiboro, reflected: "A tradition started in Strathmore from the very beginning that everyone's opinion, belief, custom, colour, creed was respected. We were taught to be mindful of one another and considerate. Students were encouraged to assist each other whenever possible. Hard work was a way of life.

"Another tradition I recall was respect for individual freedom. We had no written rules, no prefects or class monitors, no general supervised study. One was given the responsibility to exercise his individual freedom: to study on his own time, and to manage his life generally. I think this is one of the traditions that truly distinguishes Strathmore from similar institutions. It was in my two years there that I came to feel that I was really accountable for my actions, not because there were rules, but because a certain standard of excellence was expected of me. If I failed to achieve it, I could only blame myself."

Even today Strathmore is believed to be the only institution in Kenya without prefects or written rules. The philosophy was spelt out to teachers at the school thus: "Show a man you trust him and sooner or later he will respond to that trust. Leave a person free to act and he will usually act in a responsible manner; if he does not act responsibly, then patiently show him how he was wrong and leave him free to act again."

Strathmore continued to break social conventions with Kenya's first interracial rugby team. The Africans had never played before because rugby was a white man's game. The new team did not go unnoticed. The first match was recorded in The East African Standard on June 8 under the headline: "First Multi-racial Rugby Team Makes Debut;" and in the Sunday Nation on June 11, 1961, under the headline: "An Experiment on the Rugby Field." The news reached as far south as Johannesburg, with the Johannesburg Stars carrying an action photograph of the Strathmore team entitled: "Study in Black and White Rugby."

The experiment forced students at Strathmore to confront hidden prejudices. "The hooker in our team was white and the props were both big African fellows," Father Gabiola explained. "After the first training session, the hooker came and said: 'I don't want to play.' 'Why not?' I asked. He did not want to say, but eventually he whispered: 'I don't want to be with the Africans so close together.' Father Gabiola burst into laughter: "Well, it was there, the mentality was there. And it was something we had to overcome. And we did overcome it."

It was not long before 80 per cent of Strathmore's students were being accepted at university. The college gained an international reputation, attracting students from all over English speaking Africa as well as from Rwanda and Zaire. It branched out, opening a school of accountancy in 1966, a lower secondary school in 1978 and a primary school in 1987.

Some current residents of Strathmore spoke about their experience. Matthew Ndegwa, who came to Strathmore in 1979, now works for the government as a civil engineer and is a co-operator of Opus Dei. "Opus Dei taught me how to get my priorities right, to do first things first and to persevere with something to the very end, to carry out my duties," he said. "I am the first born son of a family of 12. In my country a first born son must give a good example for the others. He should also use his money to help the others, to help pay for the education of the younger ones which takes more than a third of my salary. The spiritual life Opus Dei introduced me to makes it easier to cope with the 24 hours of the day. It opens up my mind to my responsibilities and helps me not to ignore them."

More than half the population of Kenya is Christian; about one third of them, Catholic. The population has been growing faster than any other country in the world, though only about 18 per cent of land is arable. Most native Kenyans still live on small farm settlements struggling to raise livestock and crops or working part time on the properties of wealthy landowners.

As you drive out of Nairobi you quickly come to tea and coffee plantations where native Africans labour all day under the sun to earn a modest wage. The women in particular have a hard lot. You see them struggling along the side of the road under huge loads. Further inland where the countryside is dryer, hotter, dustier, where the earth has to be worked hard before it will give even the most meager returns, life is harder still. Many black Africans there live in thatched huts on bare earth floors as their people have done for centuries. They are nomads, continually migrating with their livestock and their few worldly possessions in search of grazing land and water.

For those who move to the city, it is a difficult transition. Regular work schedules, the faster pace and the impersonal way of life are difficult to adjust to. And there is the problem of the unequal sharing of wealth. The extent of this problem was brought home to me while traveling on a ratty old bus from the airport into Nairobi. It was not a bus that whites normally used. All the passengers were blacks.

From the bus you could see the shanty houses and claustrophobic housing developments where poor blacks lived. The little free land in these areas, including traffic islands, was used for sambas (the traditional Kenyan vegetable patch). The sea of faces waiting at each bus stop grew as you approached the city centre until there seemed to be hundreds of men, women and children trying to get on. It was a Saturday morning and on the footpaths you saw row after row of wretched stalls, sometimes consisting of as little as a few used vinyl belts on a piece of old cloth.

On the other side of town where the whites and wealthy blacks lived, things were different. The houses were impressive, even by the standards of developed countries. They were large and airy, the gardens pleasant, the driveways long and the hedges high. It is this contrast between rich and poor which Kenya must fight to overcome.

So far the country has managed to avoid the major political or social upheavals of other African nations; but there are no guarantees about the future. Security can only come with social justice and a national spirit which avoids large class distinctions. An essential part of social justice as it is promoted by Catholic moral teaching—and therefore by Opus Dei—is the free action of individuals. The Church's teaching recognises that good structures can never be enough to ensure social harmony and justice. No matter how good structures are, corrupt and selfish individuals can defeat them. On the other hand good citizens can succeed in making even a society with faulty structures work, the injustice of the system being counteracted by the spirit of individuals.

Over lunch in Nairobi I spoke with Wilson Kalunge, an assistant manager with an oil company and a member of Opus Dei. "One of the things which attracted me to Opus Dei was that here were people from other countries, but people who had a lot more concern for the development of this country than many of us. It was clear these people were the way they were because of the formation they had received. In Opus Dei I have learned that unless Kenyans become more concerned about the development of others some will end up wealthy while others among their countrymen are left far behind, struggling to survive. Either we accept our duties or we will end up with a classed society."

Kianda College, the first multi-racial educational centre for women in East Africa, is another project of members of Opus Dei in Nairobi. In the beginning there were only 17 students and they were all European. When the first application came from an Asian girl, the neighbours refused to consent. Again there was the problem of finding non segregated land. A site was eventually found on Waiyaki Way, 10 kilometres outside the centre of Nairobi, and Kianda became the first integrated secretarial college for women in the country. The fact was heavily publicised. One newspaper article said if anyone saw girls of different colours walking on the streets together they could be sure they were from Kianda College.

The often hostile reaction made life difficult; but racial discrimination was not the only pressure Kianda had to deal with; there was the question of sexual discrimination. In the early 1960s most African women, if they had jobs at all, had the worst; they were poorly paid; their living conditions and clothes were poor. The fees for a secretarial course were more than they could afford. Kianda was able to talk large firms into establishing a system of sponsorships. The new opportunity enabled the girls to find a career for themselves and to help support their often poverty-stricken families and clans. When independence came in 1963 Kianda was the only college training Africans.

Kianda has similar aims to Strathmore and has faced similar challenges. In 1966 it started a residential college for students who were new to Nairobi and had nowhere to stay. The more than 5000 students who have passed through came from all over East Africa, Ethiopia, Zambia, Sudan, Nigeria, Lesotho and Rwanda. Up to 17 nations have been represented at any one time, moving Kenya's Sunday Nation newspaper to comment in 1980: "Today the pan-African status of Kianda is a model for other African countries." In 1977 Kianda opened a high school. The Daily Nation noted in 1984 that the school took only seven years to become one of the nation's top 10 schools.

One goal of Kianda, as with Strathmore, has been to help students overcome racial and tribal differences and to build strong characters. Students are encouraged to read widely and to improve their cultural background. Kianda's philosophy is that Kenya needs not only secretaries with fast shorthand and typing, but mature individuals with initiative, personality and responsibility. As a principal of the college, Miss Olga Marlin, described it: "people who can run an office, not just type letters." Some of the students have become teachers at the college. Others run businesses, such as data processing firms, shops and commercial farms.

Miss Marlin, who came to Nairobi to help establish Kianda in 1960, said Kianda did not stop at giving students a sound professional formation, but helped those who were practising Christians to improve their Christian life so that it permeated everything they did. "Monsignor Escriva often warned against the danger of separating these two aspects," she said, "living a kind of double life, with God for Sundays and special occasions, on the one hand, and one's professional and social life, on the other." Miss Marlin's successor, Miss Constance Gillian, outlined some of the qualities Kianda encouraged in its students, including generosity, inner strength and calmness, tenacity and positive thinking.

Mrs. Irene Njai grew up in a rural area, but won a scholarship to study social work in Italy. She became a social worker, but when we met she was working as an airline ticketing officer because she said she could not bring herself to accept government policy promoting contraception. "When I met up with Opus Dei I learnt about turning your work into prayer. I had been a Catholic so long, nobody had ever told me about this. I was told you should pray, but never that work could be turned into prayer; that you could say, I offer this work from eight to ten o'clock to God for such and such a thing. I felt I was being guided in a special way. It was really very beautiful.

"Another thing I am grateful to Monsignor Escriva for is this idea of marriage as a vocation. For example, his praise for human love. I have never heard it from anybody else. I had read quite a lot of books before I came to Opus Dei, but I never came across anybody who asserted marriage was a vocation as Monsignor Escrivá did. Nobody else has ever talked to me about this in the same way, showing me how to use the married life as the means for my salvation and my husband's salvation. And also there is the idea that we are the heart of the family and we need to be at the service of other people. As Monsignor Escrivá used to say: 'To put our hearts on the floor for the others to walk a bit more comfortably."

The experience in Kenya highlights something important about Opus Dei: why it can be controversial in some countries, but not in others. It is not because Opus Dei differs from country to country—it is always the same. The real reason is that standards of morality vary; supporting equal rights for women in the 20th Century is bound to get you into trouble in countries where women are kept out of the workplace. But it will also attract opposition in those countries, some of them developed countries, in which women are denied the choice of being full time mothers and homemakers.

(This is a somewhat condensed version of the article as originally published)