In The Way, Saint Josemaria wrote, “Force yourself, if necessary, always to forgive those who offend you, from the very first moment. For the greatest injury or offence that you can suffer from them is as nothing compared with what God has pardoned you.” (no. 452)

This point actually tells us the story of Saint Josemaria’s own life. Previously, he had written in a personal notebook, “I will force myself, if necessary, always to forgive anyone who offends me, from the very first moment, because however great the injury or offence they cause me, God has forgiven me even more.”

“My son, it is hard, but you have to learn how to forgive.”

Other points in The Way speak about how God forgives us (nos. 262, 267, 309, 436). And now St Josemaria shows us how, as in the parable of the two debtors (Matt 18:23-35), God’s forgiveness is the basis for our forgiving our brothers and sisters, which is one of Jesus’ most characteristic teachings.

This article gives some examples of how St Josemaria practised forgiveness himself and said sorry, asking forgiveness of others. The excerpts are taken from the book The Man From Villa Tevere by Pilar Urbano.

Forgiving

St Josemaria practised, and taught his children in Opus Dei to practise, a reaction he summarised in five steps, patient but not passive ones: “pray, keep silent, understand, forgive ... and smile.” This was not intended as a sort of pain-killer; he was guiding them towards an attitude of great fortitude.

Mercedes Morado and Begoña Alvarez, who were among those who worked with Monsignor Escriva for years, wrote that his spirit of forgiving, forgetting and understanding towards those who slandered him was something that grew progressively, up to the point where he could say in all simplicity, “I don’t feel any resentment towards them. I pray for them every day, just as hard as I pray for my children. And by praying for them so much, I’ve come to love them with the same heart and the same intensity as I love my children.”

He was putting onto paper something of his own personal experience when he wrote, “Think about the good that has been done you throughout your lifetime by those who have injured or attempted to injure you. Others call such people their enemies. (...) You are nothing so special that you should have enemies; so call them ‘benefactors.’ Pray to God for them: as a result, you will come to like them.”

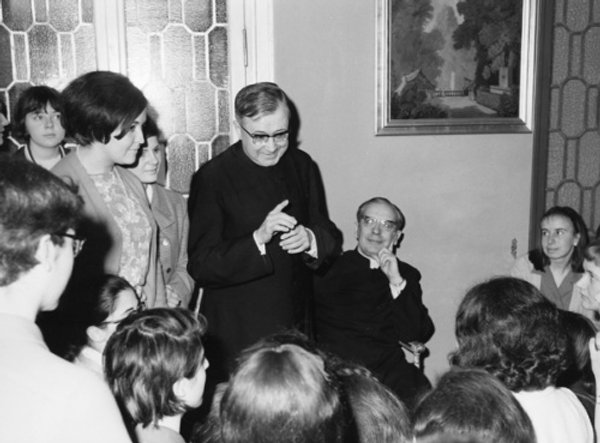

In 1962, Rafael Calvo Serer went to see him in Rome. He unburdened his heart and told him about the calumnies and persecutions he was being subjected to by certain petty officials of the Franco regime. Monsignor Escriva listened and then said, “My son, it is hard, but you have to learn how to forgive.”

He was silent for a little and then, as if thinking aloud, he added, “I didn’t need to learn how to forgive, because God has taught me how to love.”

Asking for forgiveness

St Josemaria did not care whether he lost merit in other people’s eyes, or ran the risk of lowering his authority by asking for forgiveness when he realised he was wrong or had been carried away by the first impulse of his strong character.

One day in Madrid in 1946, he went into the catering department of the Diego de Leon residence in the middle of the morning. It looked a mess: a cupboard door was half open; another cupboard was all untidy inside; the shopping had not been put away in the larder but was still in baskets and bags; and there was a pile of dirty dishes in the sink. It did not look like an Opus Dei Centre at all. Father Escriva, much upset, called for the director, but she was not in. Flor Cano, another woman of the Work, came instead received the full flood of Father Escriva’s protest.

“This can’t be allowed! It just can’t! Where is your presence of God while you’re working? You have to do things with much more sense of responsibility!”

Without realising it, Father Escriva had been raising and hardening his voice. Suddenly he stopped and was silent for an instant.

Then immediately, in a completely different tone, he said, “Lord ... forgive me! And you, my daughter, forgive me too.”

“Father – please – you’re absolutely right!” said Flor.

“Yes, I am, because what I’m saying is true,” he responded. “But I ought not to have said it in that tone of voice. So please forgive me!”

On another occasion in Rome he reprimanded Ernesto Julia on the intercom for not doing an important job. Ernesto did not protest or make any excuses. Shortly afterwards, someone informed Monsignor Escriva that Ernesto had not known about the matter because he had not been asked to do it. That very instant, without delaying a second, Monsignor Escriva picked up the intercom again to speak to Ernesto, and asked him to come to the place where the two buildings, Casa del Vicolo and Villa Vecchia, met.

When Ernesto got there he found Monsignor Escriva waiting for him with his arms wide open and a gesture of opening his heart wide too, in welcome. And with an engaging, affectionate smile he said, “My son, I’m sorry. I beg your forgiveness and restore your good name to you!”

It hurt him to leave anyone feeling hurt, so he never delayed healing any wound he might have caused inadvertently. He was quick and generous whenever he needed to put something right or ask for forgiveness.

One day in January 1955, also in Rome, while some students of the Roman College were chatting with Monsignor Escriva in a corridor in Villa Tevere, Fernando Acaso came by. Monsignor Escriva asked him if he had collected some furniture which was to due be placed near some stairs. Fernando gave an evasive, roundabout reply without making it clear whether the furniture was in the house. Monsignor Escriva interrupted him, “But have you brought it home, or not?”

“No, Father,” said Fernando.

Monsignor Escriva then told all of them there that they ought always to be “sincere and direct, unafraid of anything or anybody” and “without making excuses, because no one’s accusing you!”

At that moment along came Don Alvaro, looking for Fernando Acaso. He greeted everyone and said directly to Fernando, “Fernando, you can pick up the furniture whenever you like; there’s money in the bank for it now.”

“I went to Our Lord to ask him to forgive me, and now I’ve come to say sorry to you.”

Monsignor Escriva then realised that this was the reason for Fernando’s elusive explanation. Immediately, in front of everyone, he apologised. “Forgive me, my son, for not listening to your reasons. I can see that it wasn’t your fault. With your attitude you’ve given me a splendid lesson in humility. God bless you!”

In the summer of that same year, 1955, Monsignor Escriva went to Spain and spent a day in Molinoviejo with a big group of his sons in the Work who were doing a course there and having a rest.

A group of them were talking together outside the front door, which gave on to a pine wood. Monsignor Escriva saw Rafael Caamaño, who had just come back from Italy where he had done a three-year course in naval engineering, and, suddenly remembering something, he beckoned him and Javier Echevarria over to a stone fountain nearby, among the trees.

When the three were together, Monsignor Escriva said to Caamaño, “Rafael, I have to beg your pardon for maybe having scandalised you that time by not giving money to the beggar. I needed to tell you that that’s not my spirit. Although I never carry any money, I could have, I ought to have asked one of you to give some coins to that poor man. Now you know: the Father did wrong and begs your forgiveness.”

Rafael said nothing; he was astonished and confused. He could not remember what episode Monsignor Escriva was referring to. Only much later, and having thought it over laboriously, he managed to recall the event. Some months or maybe a year previously, he had gone with Monsignor Escriva and two other people of the Work on a drive in the outskirts of Rome. They had stopped to have a coffee in one of the castelli. While they were there a beggar came forward asking for alms, and with a vague gesture of refusal they had given him to understand they had no money or were not going to give him any. Recalling it at this time, Caamaño recognised Monsignor Escriva’s sensitive conscience and realised that this commonplace event had touched Monsignor Escriva unforgettably, like a moral debt he had an absolute need to atone for: “I needed to tell you ... the Father did wrong.”

After all, Monsignor Escriva had made the resolution years before “not to spend five cents if a beggar in my position would not spend them”!

One day in Villa Tevere Monsignor Escriva went into the office of the Secretary General of the Work. Speaking to two or three of the people working there, he corrected some errors which they had introduced into a document. It was no mere question of literary style; by saying one thing instead of another, they had misrepresented the very spirituality of Opus Dei. After making plain in no uncertain terms the far-reaching consequences such mistakes could have, he left the room.

After a while he came back, looking peaceful and joyous. “My sons,” he said, “I’ve just been to confession to Don Alvaro, because what I said to you before was something I had to say, but I shouldn’t have said it the way I did. So I went to Our Lord to ask him to forgive me, and now I’ve come to say sorry to you.”

Another time he was hurrying along a corridor when one of his spiritual daughters, who happened to be there at that moment, tried to stop him with some question which had nothing to do with anything; it was neither the time nor the place for it. Hardly even slowing his pace, he shrugged his shoulders and said, “How should I know? Ask Don Alvaro!”

Later on that day, the same girl was tidying some things in the hall of Villa Vecchia, as Monsignor Escriva and Don Alvaro went by. They stopped for a moment, and Monsignor Escriva said, “I’m sorry, my daughter, for having answered you as I did earlier on. Those of you who live with me have so much to put up with!”