Marikina is a city with nearly half a million residents on the eastern boundary of Metro Manila. Long known as the country’s shoe capital for its quality footwear — an industry that traces its roots to the late 1800s — the city is now dotted with commercial, manufacturing and residential developments. It is a major contributor to the economy of the nation's capital region, which accounts for a third of the country’s economic output.

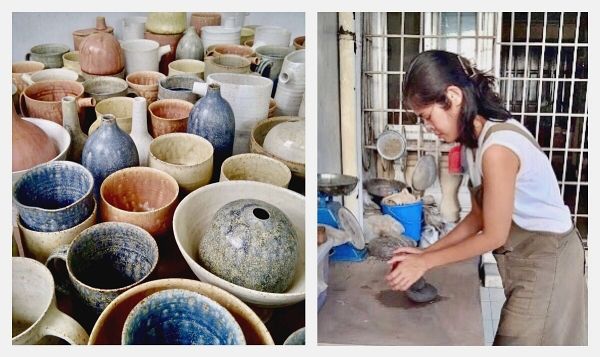

Marikina has become home to a wide variety of residents — from the likes of my late grandfather, a doctor who served those with less in life; to drivers of passenger tricycles (known locally as trikes) that have been an indispensable means of transport for the bulk of the city's commuting public; and to me, a ceramics artist who works on sculptural and functional pieces in my grandparents' garage in barangay San Roque (Marikina).

I go by the Instagram handle @taongputik (@clayperson) because clay is my medium. I use my hands to pinch, press, and roll the clay, working it to the desired shape in much the same way as a baker kneads dough.

In this garage-workshop, I had grown accustomed to the sound of trikes traversing the road the whole day. The humming and revving of their engines would drown the banter and laughter of the drivers at the terminal outside my gate waiting for their next passengers. Occasionally, some of these drivers would strike up a conversation with me as I worked on my creations.

Then COVID-19 struck, and the bustling life in our community grounded to a halt.

March 2020 was the beginning of an “Enhanced Community Quarantine.” People were confined to their homes. Offices, business establishments, and public destinations were closed. The streets fell silent.

AWAKENING

It was four months later, in July, when some restricted travel was allowed. I saw that the queues of empty trikes at the terminal were much longer, since fewer people stepped out of their homes. And the trikes were off the streets earlier, at dusk, due to the imposed curfew. No passengers, no income.

It dawned on me that these trike drivers were among the many who had lost their livelihood overnight. I had a general idea of the situation from the news and stories from friends and acquaintances, but I was not aware of how serious the impact was on the lives and families of these daily wage earners.

Marikina is classified as a first-class city with an annual income of P1.951-billion. I learned that this is due largely to the business registrations and real property taxes coming from its 16,677 enterprises and 112,727 households. What this pandemic did was to lay bare the economic vulnerability of its working class population. This same situation is mirrored in cities and municipalities nationwide.

The realization of the plight of the drivers led me to raise money to give them some assistance. I sold some of my artworks for this purpose. A more direct engagement, I thought, would mean big opportunity losses for me. Up to that time, I had felt -- like many of my artist-friends, I learned later on -- that I was not essential in addressing the social plight of the community.

In November of 2020, my parents and their friends organized 3 separate Christmas food basket and rice distribution activities for 55 jeepney drivers plying the route between barangay Tumana (Marikina) and Balara (Quezon City).

The joy written on the beneficiaries’ faces was contagious, and it made me ask: “Couldn’t I do something similar for the trike drivers in my place? Was God asking me to go beyond my comfort zone? What comes after this? Do I carry on as usual, making and selling my artworks?”

I recalled what St. Josemaria wrote in Christ is Passing By: “A man or a society that does not react to suffering and injustice and makes no effort to alleviate them is still distant from the love of Christ’s heart.”

The thought of the families of the trike drivers in my neighborhood going hungry kept calling on me.

TURNING POINT

I decided to act.

I had been selling my works online. I started to set aside a portion of each sale to fund my social project. I composed a personal motto: “Mag-masa para sa namamasada para patuloy silang makapaglingkod sa masa” (Work the clay for the trike drivers so that they can continue serving the commuting masses).

To my surprise, within a week, I had raised enough cash to buy a sack of rice each for the 25 drivers at the terminal outside the house. That would tide them through for some days. Then I learned that there were 67 other drivers at a terminal further away.

I decided to go public with my fund raising. I posted the project online and messaged my family and friends to help. The network that social media provided gave us much-needed traction, which enabled us to generate resources to operate for several weeks. Donations came in cash and in kind from family, relatives, friends, and even from my clients.

As we were distributing rice packs last April, I recall that I was pondering how long we could sustain this assistance to the community.

When I heard in May that "community pantries” popped up in different districts and villages in the Metro as a response to the food crisis in families, I did not hesitate to put up my own that same afternoon with a hastily scribbled signboard.

There were a few sacks of rice left and a little money to buy bread, noodles, and canned goods to get things started. The San Roque Community Pantry began on May 17, 2021.

I explained the concept to my trike driver-neighbors. “Magbigay ayon sa kakayahan. Kumuha batay sa pangangailangan” (Give according to one’s capacity. Take according to one’s needs). It was community sharing.

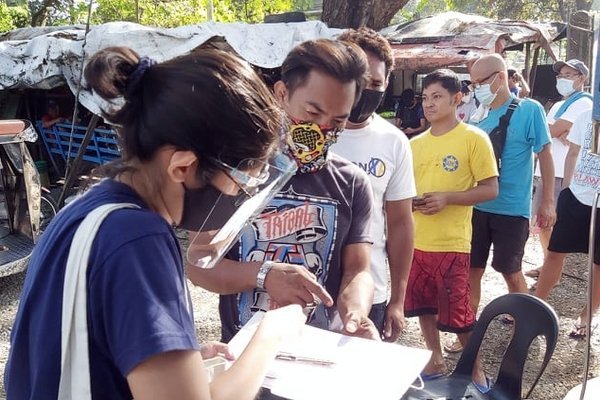

The pantry was to be located by a commuter waiting shed close by. I asked them to help man and organize the operations, and I can say that they more than complied.

HELPING THEM HELP THEMSELVES

I tried to be present whenever they opened the pantry in the morning. They received the goods, sorted them, repacked them, arranged them, handed them out, and controlled the people in the queues.

The trike drivers’ involvement left a deep impression in me. They made sure that those who had lost their jobs, those who had bigger families, and those who had persons disabled in their homes got enough supplies. They would deliver goods to the homes of the sick and the elderly.

I grew up in an environment very different from theirs. They knew the situation of their peers, so I gave a lot of weight to their recommendations on how to run things. This truly became a community project for the benefit of the community.

In the beginning our supplies would be wiped out within 30 minutes of opening, and we had doubts about whether we could sustain our operations. But I recalled the first donation of P50 and a loaf of bread for this pantry project. It reminded me to trust in divine providence and in the kindness of people.

In time, some of those who had benefitted from the pantry started donating whatever they could to keep it going — sacks of mongo shoots here, a tray of okoy (fried shrimp cakes) there, stir-fried noodles, and other small items.

It amazed me to learn that, on their own, the trike drivers and their neighbors started rounds of ambagan (contributing whatever small amounts they could among themselves) to purchase more supplies. I realized then that they were the key to resolving the community's plight.

Our “community pantry” grew from a humble table outside the house to a line of tables filled with goods enough to supply up to as many as 400 people in a day. Our operation managed to accommodate street sweepers and ambulant vendors, as well as trike drivers from other areas.

Our mutual trust and respect for each other in the neighborhood enabled us to have a continuing flow of food and essential items. At the same time, our operation served as a vehicle for concerned individuals, who had more in life, to give to those who were in need.

With the recent Delta variant surge however, we had to suspend activities to avoid “super-spreader” events.

JUST THE BEGINNING

It is clear to me that the “community pantry” concept will not solve the roots of hunger. I want to see these efforts transitioning into larger programs.

Our operations are, by no means, perfect despite the many adjustments we have made. There’s no single formula for running a “community pantry” since each community has its own profile, specific needs, resources, and capabilities.

We found ways to improve our system as we continued to understand the people’s needs. It’s important to get to know the residents, to listen to them, and to adjust.

Before our family outreach activity for the jeepney drivers last November, my parents reminded us siblings that there is a world of difference between socio-civic work and corporal works of mercy. Both are good works. The works of mercy though echo Matthew 25:35-40: “For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, a stranger and you welcomed me… Amen, I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.”

I am thankful to have encountered Christ in the beneficiaries, donors and volunteers of our “community pantry”.

Marianella Mendoza

marianellaluisa@gmail.com