1. The Real Eucharistic Presence

During the celebration of the Eucharist, the Person of Christ becomes present—the Word made flesh, who was crucified, died and rose for the salvation of the whole world—in a mysterious, supernatural and unique form of presence. The source of this doctrine can be found in the very institution of the Eucharist, when Jesus identified the gifts He was offering with his Body and his Blood (“this is my Body … this is my Blood"), that is, with his physical being inseparably united to the Word, and thus with his entire Person.

Christ Jesus is present in many ways in his Church: in his word, in the faithful when they pray (cf. Mt 18:20), in the poor, the sick, the imprisoned (cf. Mt 25: 31-46), in the sacraments and especially in the person of the ministerial priest. But above all He is present in the Eucharistic species (cf. CCC , 1373).

What makes the Eucharistic presence of Christ unique is the fact that the Blessed Sacrament truly, really and substantially contains the Body and Blood together with the Soul and Divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, true God and perfect Man, the same who was born of the Virgin Mary, died on the Cross and now is seated in Heaven at the right hand of the Father. “This presence is called 'real' – by which is not intended to exclude the other types of presence as if they could not be 'real' too, but because it is presence in the fullest sense; that is to say, it is a substantial presence by which Christ, God and man, makes himself wholly and entirely present" ( CCC , 1374).

The word “substantial" endeavours to capture the reality of Christ's personal presence in the Eucharist. This is not simply a “figure," able to “signify" and help us to think about Christ, present in reality somewhere else, in Heaven. Nor is it a mere “sign" through which we are offered the “saving strength," the grace, which comes from Christ. Rather the Eucharist is an objective presence, the real being, the substance of the Body and Blood of Christ, that is, of his entire Humanity—inseparably united to the Divinity through the hypostatic union—though veiled by the “species" or appearances of bread and wine.

Hence, the presence of the true Body and the true Blood of Christ in this sacrament “cannot be apprehended by the senses, says St Thomas, but only by faith , which relies on divine authority" ( CCC , 1381). This is expressed very well in the following verse from the hymn Adoro Te attributed to St. Thomas Aquinas himself: Visus, tactus, gustus, in Te fallitur / Sed audito solo tuto creditur./ Credo quidquid dixit Dei Filius/ Nil hoc verbo Veritatis verius. (Sight, touch, taste in You fail / Only hearing can be relied on / I believe whatever God the Son says / There is no truer word than Truth himself).

2. The Transubstantiation

Christ's real and substantial presence in the Eucharist requires an extraordinary, supernatural and unique change. This change is grounded in our Lord's clear words: Take, eat; this is my Body … drink of it, all of you, for this is my Blood of the new covenant (Mt 26: 26-28). These words require that the bread and wine cease to be bread and wine and are converted into the Body and Blood of Christ, because it is impossible for the same thing to be simultaneously two different things, bread and the Body of Christ, wine and the Blood of Christ.

As the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches, “The Council of Trent summarizes the Catholic faith by declaring: 'Because Christ our Redeemer said that it was truly his body that he was offering under the species of bread, it has always been the conviction of the Church of God, and this holy Council now declares again, that by the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood. This change the holy Catholic Church has fittingly and properly called transubstantiation'" (CCC , 1376). Nevertheless the appearances of the bread and wine, that is, the Eucharistic “species," remain unaltered.

Although what the senses truly perceive are the appearances of bread and wine, by the light of faith we know that what is really contained under the veil of the Eucharistic species is the substance of the Body and Blood of our Lord. Thanks to the permanence of the sacramental species of bread, we can say that the Body of Christ, his entire Person, is really present on the altar or in the ciborium or in the tabernacle.

3. Properties of the Eucharistic Presence

Christ's mode of presence in the Eucharist is a marvelous mystery. According to Catholic faith Jesus Christ is entirely present, with his glorified Body, under each of the Eucharistic species, and also in each fragment that results from the division of the species, such that even though the bread may be broken in pieces Christ is not divided. (cf. CCC , 1377). [1] This is a unique mode of presence, one that is invisible and intangible; it is also permanent: once the Consecration has taken place, it lasts as long as the Eucharistic species last.

4. Eucharistic worship

Faith in Christ's real presence in the Eucharist has led the Church to offer the cult of latria (that is, adoration) to the Blessed Sacrament, both during the liturgy of the Mass (and therefore she asks us to genuflect or bow deeply before the consecrated species) and also outside the celebration of Mass: reserving the consecrated hosts with utmost care in the Tabernacle, presenting them to the faithful for solemn veneration, carrying the Host in procession, etc. (cf. CCC , 1378).

Reasons for reserving the Blessed Sacrament in the Tabernacle: [2]

— principally to be able to give Holy Communion to the sick and other faithful who cannot get to Mass;

— also so that the Church can offer adoration to God our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament (especially during Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, in Benediction, in the Procession with the Blessed Sacrament on the Solemnity of Corpus Christi, etc.);

— and also so that the faithful can always adore our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament, through frequent visits. As John Paul II said, “Let us be generous with our time in going to meet him in adoration and in a contemplation that is full of faith and be ready to make reparation for the great faults and crimes of the world. May our adoration never cease." [3]

There are two great liturgical feasts (solemnities) on which this Sacred Mystery is celebrated in a special way: Holy (or Maundy) Thursday, the commemoration of the institution of the Eucharist and Holy Orders, and Corpus Christi, the solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ, dedicated especially to the adoration and contemplation of our Lord in the Eucharist.

5. The Eucharist, Paschal Banquet of the Church

5.1 Why is the Eucharist the Paschal Banquet of the Church?

“The Eucharist is the Paschal Banquet in as much as Christ sacramentally makes present his Passover [his 'passing' from this world to the Father through his passion, death, resurrection and glorious ascension [4] ] and gives us his Body and Blood, offered as food and drink, uniting us to himself and to each other in his sacrifice" ( Compendium , 287)

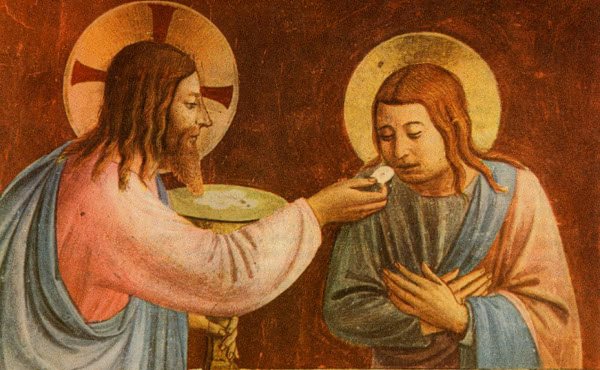

5.2 Celebration of the Eucharist and Communion with Christ

“The Mass is at the same time, and inseparably, the sacrificial memorial in which the sacrifice of the Cross is perpetuated and the sacred banquet of communion with the Lord's Body and Blood. But the celebration of the Eucharistic sacrifice is wholly directed towards the intimate union of the faithful with Christ through communion. To receive communion is to receive Christ himself who has offered himself for us" (CCC , 1382).

Holy Communion, ordained by Christ (Take, eat … drink of it, all of you … (Mt 26:26-28. Cf. also Mk 14:22-24; Lk 22:14-20; 1 Cor. 11:23-26) forms part of the basic structure of the Eucharistic celebration. Only when Christ is received by the faithful as the food of eternal life does his making himself food for us achieve its deepest meaning, and the memorial He instituted is carried out. [5] This is why the Church so ardently recommends sacramental Communion to all who take part in the Eucharistic celebration, when they fulfill the necessary conditions to receive the Blessed Sacrament worthily. [6]

5.3 Necessity of Holy Communion

When promising us the Eucharist, Jesus stated that this food is not only useful, but that it is necessary if his disciples are to have life. Truly, truly I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you (Jn 6:53).

Just as natural food keeps us alive and gives us strength in this world, similarly the Eucharist strengthens in us the life in Christ received at Baptism, and gives us strength to be faithful to our Lord on this earth until we reach the Father's house. The Fathers of the Church saw in the bread and water that the angel gave Elias a “type" or foreshadowing of the Eucharist (1 Kg 19:1-8).After receiving these gifts, Elias recovered his strength and was able to fulfill God's mission.

Holy Communion, then, is not just a necessity for some of the faithful more especially involved in the Church's mission, but rather it is a vital necessity for everyone. Only those who nourish themselves on Christ's own life can live in Christ and spread his Gospel.

Christians should always have the desire to receive Holy Communion, just as the desire to achieve our last end should always be present in our life. This desire to receive Communion, explicit or at least implicit, is necessary for attaining salvation.

Moreover, the actual reception of Holy Communion is necessary, with the necessity stemming from Church law, for all who have reached the age of reason “The Church obliges the faithful to take part in the Divine Liturgy on Sundays and feast days and, prepared by the sacrament of Reconciliation, to receive the Eucharist at least once a year, if possible during the Easter season" ( CCC , 1389). This Church law is just a minimum, which will seldom be enough to develop a genuine Christian life. That is why “the Church strongly encourages the faithful to receive the holy Eucharist on Sundays and feast days, or more often still, even daily" ( CCC , 1389).

5.4 The Eucharistic minister

The ordinary minister of Holy Communion is the bishop, the priest or the deacon. [7] The acolyte is a permanent extraordinary minister. [8] Other members of the faithful to whom the Ordinary of the diocese has given the faculty of distributing Communion can be extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion when it is judged necessary for the pastoral good of the faithful and there is no priest, deacon or acolyte available. [9]

“It is not licit for the faithful to take by themselves and still less to hand from one to another the sacred host or the sacred chalice." [10] Holy Communion has the value of a sacred sign, a sign that should make clear that the Eucharist is a gift from God to man. Hence under normal conditions, when the Eucharist is distributed, there should be a distinction between the minister who distributes God's gift, offered by Christ himself, and the subject who receives it with gratitude, faith and love.

5.5 Dispositions to receive Holy Communion

Dispositions of the soul

To receive Holy Communion worthily, one must be in the state of grace. Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks of the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner , proclaims St Paul, will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord. Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself (1 Cor 11: 27-29). Anyone with a grave sin on their conscience, however contrite they may be, must first go to Confession before receiving Communion (cf. CCC , 1385).

To receive Holy Communion fruitfully, besides being in the state of grace, we need to make a serious effort to receive our Lord with the greatest possible devotion: this requires remote and immediate preparation, acts of love and reparation, adoration and humility, thanksgiving, etc.

Dispositions of the body

Interior reverence for the Sacred Eucharist should also be reflected in the bearing of the body. The Church prescribes a fast. For the faithful of the Latin rite the fast consists in abstaining from all food and drink (except water and medicines) for an hour before receiving Holy Communion. [11] Attention should also be paid to personal grooming, a suitable manner of dress, and to bodily gestures of veneration that show respect and love for our Lord, present in the Blessed Sacrament, etc. (cf. CCC , 1387).

The traditional way of receiving Holy Communion in the Latin rite—a reflection of faith and love, and of the piety of the Church over the centuries—is kneeling and on the tongue. The reasons that gave rise to this pious and ancient custom are still fully valid. One can also receive communion standing and, in certain dioceses, it is allowed—but never required—to receive the Sacred Host in the hand. [12]

5.6 Age and Preparation for First Communion

The precept regarding Holy Communion obliges all those who have reached the age of reason. Children should be well prepared, and their First Communion should not be delayed. Let the children come to Me and do not hold them back, because to such belong the Kingdom of God (Mk 10:14). [13]

For a child to receive First Communion, knowledge of the principle mysteries of the Faith is required, in accord with the child's capacity to understand, and the ability to distinguish between the Eucharistic Bread and ordinary bread. “It is primarily the duty of parents and those who take the place of parents, as well as the duty of pastors, to take care that children who have reached the use of reason are prepared properly and, after they have made sacramental confession, are refreshed with this divine food as soon as possible." [14]

5.7 Effects of Holy Communion

What food produces in the body for the good of physical life, the Eucharist produces in the soul, in an infinitely higher way, for the good of spiritual life. But whereas food becomes part of our bodily substance, on receiving Holy Communion it is we who are “transformed" into Christ. “You do not transform Me into you as food into your flesh; rather you become transformed into Me." [15] Through the Eucharist the new life in Christ begun in the believer at Baptism (cf. Rom 6:3-4; Gal 3: 27-28) is strengthened and can reach its fullness (cf. Eph 4:13), even to the point of the ideal announced by St Paul: I live, but not I; it is Christ who lives in me (Gal 2:20). [16]

Thus the Eucharist infuses Christ's way of being into us, enabling us to share in the Son's life and mission. The Eucharist identifies us with his intentions and feelings, gives us the strength to love as Christ asks us to (cf. Jn 13:34-35), in order to enkindle in all men and women the fire of divine love that He came to the earth to bring (cf. Lk 12:49). “If we have been renewed by receiving our Lord's body, we should show it. Let us pray that our thoughts be sincere, full of peace, self-giving, and service. Let us pray that we be clear and true in what we say—the right thing at the right time—so as to console and help and especially bring God's light to others. Let us pray that our actions be consistent and effective and right, so that they give off the good fragrance of Christ (2 Cor 2:15), evoking his way of doing things." [17]

Through Holy Communion God makes us grow in grace and virtue, pardons our venial sins and the temporal punishment due to them, preserves us from mortal sins and helps us persevere in doing good. He draws us closer to himself (cf. CCC , 1394-1395). But the Eucharist was not instituted for the forgiveness of mortal sins; that is proper to the sacrament of Confession ( CCC , 1395).

The Eucharist draws all Christian faithful into unity with the Lord, bringing about the unity of the Church, the Mystical Body of Christ (cf. CCC , 1396)

The Eucharist is the “pledge of future glory," that is, of the resurrection and eternal life and happiness with our triune God, with the angels and all the saints. “Having passed from this world to the Father, Christ gives us in the Eucharist the pledge of glory with him. Participation in the Holy Sacrifice identifies us with his Heart, sustains our strength along the pilgrimage of this life, makes us long for eternal life, and unites us even now to the Church in heaven, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and all the saints" ( CCC , 1419).

Angel Garcia Ibañez

Basic Bibliography

Catechism of the Catholic Church , 1373-1405.

John Paul II, Enc. Ecclesia de Eucharistia , 17 April 2003, 15, 21-25, 34-46.

Benedict XVI, Apost. Exhort. Sacramentum Caritatis , 22 February 2007, 14-15, 30-32, 66-69.

Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, Instruction, Redemptionis Sacramentum , 25 March 2004, 129-160.

Recommended Reading

St Josemaria Escriva, Homily, “On the Feast of Corpus Christi," in Christ Is Passing By , 150-161.

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, God Is Near Us: The Eucharist, the Heart of Life , Ignatius Press.

Footnotes:

[1] “Since Christ is sacramentally present under each of the species, communion under the species of bread alone makes it possible to receive all the fruit of Eucharistic grace" (CCC, 1390).

[2] See Paul VI, Enc. Mysterium Fidei , 56; John Paul II, Enc. Ecclesia de Eucharistia, 29; Benedict XVI, Apost. Exhort. Sacramentum Caritatis , 66-69; Instr. Redemptionis Sacramentum , 129-145.

[3] John Paul II, Letter, Dominicae Cenae, 3.

[4] The noun “passover" (and the adjective “paschal") comes from the Hebrew word meaning passage or transit. In the book of Exodus (Ex 12:1-14 and Ex 12:21-27), it is linked to the “passing over" of the Lord and his angel during the night of the liberation of the chosen People (when the Passover meal is celebrated), and the transit of the People of God from the slavery of Egypt to the freedom of the promised land.

[5] This does not mean to say that the Eucharistic celebration is invalid if all the faithful present do not go to Communion or that they must go to Communion under both species. This is necessary only for the celebrant.

[6] Cf. Roman Missal, Institutio Generalis ,80; John Paul II, Enc Ecclesia de Eucharistia , 16; Instr. Redemptionis Sacramentum, 81-83, 88-89.

[7] Cf. Code of Canon Law, 910; Institutio Generalis , 92-94.

[8] Cf. Code of Canon Law, 910,2; Institutio Generalis , 98; Redemptionis Sacramentum , 154-160.

[9] Cf. Code of Canon Law, 910, 2 and 230, 3; Institutio Generalis , 100 and 162; Redemptionis Sacramentum , 88 .

[10] Redemptionis Sacramentum , 94; Institutio Generalis , 160.

[11] Cf. Code of Canon Law, 919,1.

[12] Cf. John Paul II, Letter, Dominicae Cenae , 11; Institutio Generalis , 181; Redemptionis Sacramentum , 92.

[13] Cf. St Pius X, Decree, Quam Singulari , 1: Denzinger 3530; Code of Canon Law, 913-914; Redemptionis Sacramentum, 87.

[14] Code of Canon Law, 914; cf. CCC , 1457.

[15] St Augustine, Confessions , 7,10.

[16] If the saving effects of the Eucharist do not achieve their plentitude all at once “it is not because of any limitation of Christ's power, but rather through the defective devotion of man" (St. Thomas Aquinas, S.Th., III, q. 79, a.5, ad 3).

[17] St Josemaria Escriva, Christ Is Passing By , 156