How was it that a farmer’s son from central Alberta ended up meeting Opus Dei in Boston, Massachusetts?

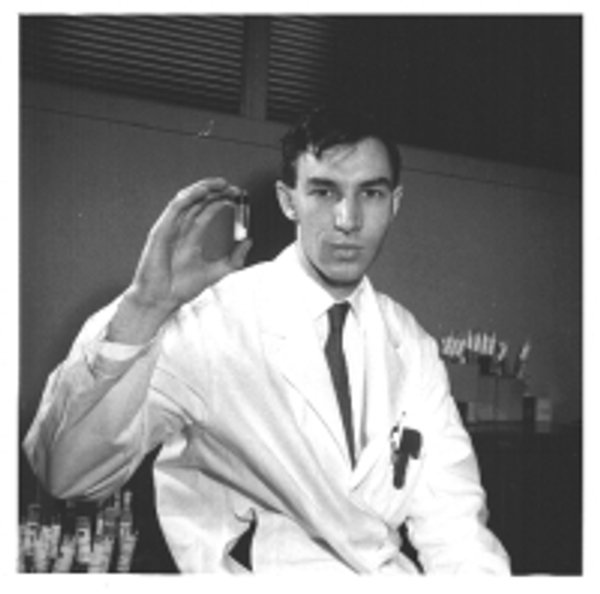

By hindsight, it’s easy to see that it was clearly providential. There was a professor of chemistry, Reuben Sandin, at the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, who was like a father (and a grandfather!) to the chemistry undergraduates who were close to finishing. One day, early in my last year, he came up to me while I was working in the laboratory, and asked, “How is your math, Joe?” Not knowing why he was asking, I simply answered, “Well, it’s alright, Dr. Sandin.” “Because,” he went on, “I think you ought to go to MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for your graduate studies. You write to Art Cope – he’s the chairman of the chemistry department – and tell him I suggested it.” And Professor Sandin’s reputation as an educator was such that if he recommended a person, that person would be accepted.

Over the previous 20 years he had shepherded a good number of students into different graduate schools. But - this is where providence appears – as far as I know, I was the first person whom he had ever sent to the Eastern United States; he usually had them going to the Midwest or the West. And in the chemistry department at MIT was another graduate student, Bob Yoest, who put me in touch with a centre of Opus Dei in Boston. And that’s how the connection was made.

Let’s back up a bit. Could tell us about your origins? They might be of interest to our readers.

With pleasure. My parents, Ted and Marion Atkinson, both came from farming backgrounds, so when they were married in 1933 they moved onto a quarter section of farmland (160 acres), near Mallaig, about 200 km. northeast of Edmonton, the capital of Alberta. One interesting item was that my sister Luella (1 year younger) and I were home-schooled long before it was called home-schooling. The provincial Department of Education had a whole system of correspondence courses set up for children who lived too far from a school to attend. So every month, we would do lessons under the supervision of our parents, these were mailed in, and new lessons sent back. In this way, we completed our first 3 years of schooling. My brother Dave (6 years younger) was able to attend regular schools from the beginning. Over the next few years, our parents moved house twice primarily to make sure that all three of their children got as good an education and upbringing as they could provide – and for that alone, we owe them a huge debt of gratitude. Finally, our family ended up in Edmonton.

Any other stories from those early years?

A couple of items. I was just nine days old when I was first exposed to French, which is pretty unusual for an Anglophone native-born Albertan. It happened when my parents took me to the Cathedral Parish in St. Paul, Alberta, to be baptized. The priest who officiated was a Francophone and asked all the questions in French. It wasn’t until 27 years later, when I started work in Montreal, that I learned enough French to be able to answer those questions. But my main memories of my childhood were those long wonderful summers on the farm, which were nothing but fun for us kids – especially when it got warm enough for us to go barefoot all the time.

So, how exactly did you come to join Opus Dei?

From a human point of view, it was a rather straightforward matter. As I mentioned above, I started attending activities at a centre of Opus Dei about a year after I arrived in Boston. My mother and father had raised all of us to have a deep love for Our Lord and His Church, the Pope and the Blessed Virgin Mary. What I learned at the centre seemed a natural continuation of that. It helped me to live my faith more deeply, not just by hearing Mass and saying the rosary, but in my studies and in my social life with my friends and colleagues. I also learned how to spread the good news of our faith to my fellow students in a natural friendly way. After a few months, the Director of the centre, Carl Schmitt (a graduate student in history at nearby Harvard University), asked me if I might want to join Opus Dei. I had not explicitly thought of that possibility, but his suggestion did not strike me as surprising or unusual. So, on January 14, 1959, over a cup of coffee in a walk-in cafeteria, I wrote a short letter to Msgr. (now St.) Josemaria Escriva, the founder and head of Opus Dei, asking to be admitted as a Numerary member.

So, smooth sailing from then on?

Well, actually, no. Within a week or two after I wrote the letter asking admission, I began to express reservations to both Carl and Fr. Bill Porras, a priest of Opus Dei. They were both very patient and, with a combination of firmness (Don’t be a cry-baby!) and understanding, helped me to realize that my so-called “reservations” might be the result of a hidden selfishness and unwillingness to commit myself unreservedly to Our Lord. I knew very well that those were the reasons behind my “objections”, and after a few months I got up the nerve to tell myself and Our Lord that I would give it an honest try, and in that way, it would become clear whether or not this was what God wanted of me. Since that time, it has been, as you say, pretty smooth sailing.

Was there any particular aspect of its spirit which struck you about Opus Dei?

Yes – the fact that our work is an explicit part of how we serve God, and for a Catholic, of how we live our faith. As I said above, I had the good fortune to have been raised in a solidly Catholic family and had developed a real love for the Church and the Pope. As I got into my studies at university, I also developed a great love for chemistry, and these two loves were on two parallel tracks, neither opposed nor competing. The spirit of Opus Dei showed me that, voilà! My chemistry was an integral part of my desire to serve God and the Church. Through it I was discovering and putting to use some of the potential in God’s material creation. In words of the founder, St. Josemaria, “…our professional vocation is an essential and inseparable part of our condition as Christians. Our Lord wants you to be holy in the place where you are, in the job you have chosen…” (Friends of God, no. 60).

Speaking of the founder, you must have had the occasion to meet him. What was your impression?

In two words: Good-humoured. I had the good fortune to have had two brief meetings with him, in 1966 in Rome and 1975 in Guatemala, a few months before he passed away. At the first meeting he was especially warm and overjoyed to meet a son of his for the first time. A simple example of his good humour came up when he asked me if anyone had yet given me a panettone (a well-known Italian sweet bread). When I told him, “No Father”, he immediately asked someone to arrange it. Then he turned to me and said jokingly, “The advantage of a gift like a panettone is that if you have any trouble with it at the customs office, you can just step aside for 10 minutes and eat it!” And he also had great fun making a little metal donkey which he gave me stand up properly in the palm of my hand.

How did your family react to your vocation? Were they supportive or did they have reservations?

My father summed up their reaction by saying, “Son, if you’re happy, we’re happy”. It should be remembered that I was almost 24 years old at the time and several thousand miles from Alberta, so they were almost certainly not expecting me to stay close to home anyway. And though they might not have completely understood my vocation at the time, they too, learned to love the Work. It was my pleasure to see both of my parents become Cooperators of Opus Dei some time before they passed away.

And how did you come to return to Canada?

That involved another major providential intervention. When I finished at MIT in 1962 the only Opus Dei centre in Canada was in Montreal. But, at that time, Montreal was the best city in the country for my type of work. The result was that after graduating in June, I was able to start work on August 1st for Merck Frosst Canada. This is the Canadian branch of the American pharmaceutical company, Merck & Co. Inc., and I worked in their Montreal research laboratories for the next 37 years. It was a thoroughly enjoyable and satisfying personal and professional experience.

You are of a completely Anglophone background, with your father born in England and your mother of Scotch and Irish descent. Did the fact that Opus Dei was founded in Spain, and that the majority of members in 1959 were Spanish, make Opus Dei seem like a Spanish or foreign institution?

It may be a surprise to some people, but such thoughts never crossed my mind. I of course learned very early on that it had been founded in Spain, and that the founder, who was still alive, was living in Rome. Why didn’t it strike me as “foreign”? I would say that it was because its spirit and message are universal, catholic. Christianity itself started in what is now Israel, but within a decade of its founder’s ascension into heaven, it was reaching out beyond those initial borders. And besides, every institution in the Church had to start somewhere, but most people nowadays don’t think of the Jesuits as Spanish or the Franciscans as Italian or the Cistercians as French – they think of them all as simply Catholic, and that’s how I always saw Opus Dei.

Any other thoughts?

Yes – I hope to reach age 93 so as to be able to celebrate the centennial of the founding of Opus Dei here on Earth in 2028.