"God is calling you to paths of contemplation," a young married man, Victor G. Hoz, was told by his confessor one day in 1941. He was amazed. He had always thought that "to be a contemplative" was for holy people given to the mystical way of life, to be aimed at only by a chosen few, by people for the most part withdrawn from the world. "But I," he writes, "was a married man, with three children, and expecting more—which was indeed what happened—and I had to work hard to support the family."

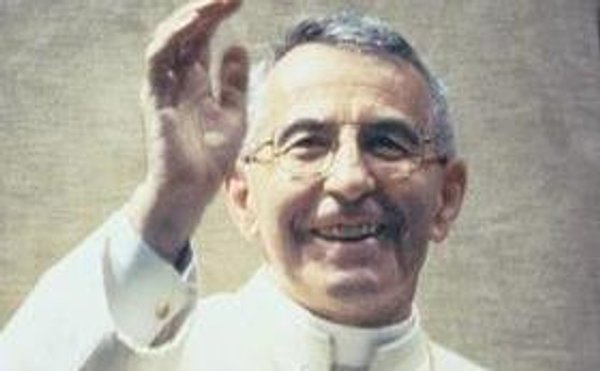

Who, then, was this revolutionary priest who was vaulting over traditional barriers, pointing out mystical goals even to married people? It was Josemaría Escrivá, a secular priest who died in Rome in 1975 at the age of seventy-three. He is best known as the founder of Opus Dei, an association which is spread throughout the world. Newspapers give it a lot of coverage, but their reports are frequently quite inaccurate.

What in fact the members of Opus Dei are, and what they do, has been explained as follows by the founder: "We are," he said in 1967, "a small percentage of priests, who have worked previously in a secular profession or trade. A large number of secular priests from many dioceses throughout the world; and a great multitude of men and women, of different countries, races and languages, who earn their living with their daily work. Most of them are married; many others are single. They share with their fellow citizens in the important task of making society more human and more just. They work on their own responsibility, shoulder to shoulder with their fellow men, experiencing with them successes and failures in the noble struggle to fulfill their duties and exercise their social and civil rights. And all this with naturalness, like any other conscientious Christian, without considering themselves in any way special. Side by side with their companions, they try to detect the flashes of divine splendor which shine through the most common everyday realities."

In less eloquent words, the "everyday realities" constitute the work which one does every day; and the "flashes of divine splendor" are those things which lead to a holy life. Msgr. Escrivá, with Gospel in hand, constantly taught: God does not want us simply to be good, he wants us to be saints, through and through. However, he wants us to attain that sanctity, not by doing extraordinary things, but rather through ordinary common activities. It is the way they are done which must be uncommon. There, in the middle of the street, in the office, in the factory, we can be holy, provided we do our job competently, for love of God and cheerfully, so that everyday work becomes, not "a daily tragedy," but rather "a daily smile."

More than three hundred years earlier St. Francis de Sales taught something along the same lines. A preacher had publicly consigned to the flames from his pulpit a book in which St. Francis had said that in certain circumstances dancing can be permissible; the book also contained a whole chapter on the “worthiness of the marriage bed." However, Msgr. Escrivá went further than St. Francis de Sales in many respects. St. Francis proclaimed sanctity for everyone but seems to have only a " spirituality for lay people” whereas Msgr. Escrivá wants a lay spirituality." Francis, in other words, nearly always suggests for the laity the same practical means used by religious, but with suitable modifications. Escrivá is more radical; he goes as far as talking about "materializing"—in a good sense—the quest for holiness. For him, it is the material work itself which must be turned into prayer and sanctity.

The legendary Baron Munchausen tells a fable of a monstrous hare that had a double set of legs: four normal ones on his belly and four more on his back. Pursued by the hounds and feeling himself about to be overtaken, he flips himself over and continues running on four fresh legs. For the founder Opus Dei the life of a Christian would be just as monstrous if he were to go about with a double series of activities: one consisting of prayers, for God; the other made up of work, relaxation and family life, for himself. No, says Escrivá, there is only one life, and it has to be made holy en bloc. That is why he speaks of a "materialized" spirituality.

Msgr. Escrivá also speaks about a good and necessary "anticlericalism," in the sense that the lay people should not imitate the methods and roles of the priests and religious, nor vice versa. I think he must have got this "anticlericalism" from his parents, and especially from his father, who was a rough gentleman, hard working, and a convinced Christian, very much in love with his wife, and always with a smile on lips. "I remember that he was always very calm," his son wrote. "I owe my vocation to him, and for that reason I am 'paternalist'." Another stimulus to his "anticlericalism" probably came from his research for his doctoral thesis in canon law. It was about the Cistercian abbey of nuns of Las Huelgas, near Burgos. The abbess there was at one and the same time a duchess, a mother superior, a prelate and the temporal governor of the abbey and the hospital, as well as of the convents, churches and dependent villages, with powers and jurisdiction which were regal and quasi-episcopal. Here was another 'monster' due to so many conflicting and superimposed duties. These tasks, heaped one on top of the other were ill-suited to become—as Msgr. Escrivá would have them—works of God. Because, he would ask, how can any work be "God's work" if it is done badly, in a hurry, incompetently? How can a bricklayer, an architect, a doctor or a teacher become holy if he is not also trying, as best he can, to be a good bricklayer, a good architect, a good doctor or a good teacher? Gilson wrote in the same vein in 1949: "They tell us that it was faith that built the medieval cathedrals. Agreed ... but geometry also played its part." Faith and geometry, faith and competent work go hand in hand for Msgr. Escrivá. They are the two wings of sanctity.

Francis de Sales had entrusted his teaching to books. Msgr. Escrivá did likewise, making use of little scraps of time. If an idea or a significant phrase occurred to him, even in the midst of a conversation, he would pull a notepad out of his pocket and jot down a word or half a line, to be used later in his writings. Apart from writing books (which are very widely read today), he dedicated himself energetically and tenaciously to promoting his great project of spirituality: organizing the association of Opus Dei. There's a proverb which says, "Give a man from Aragon a nail and he'll hammer it in with his own head." Well, Msgr. Escrivá has written, "I'm from Aragon. I'm very stubborn." He did not waste a minute. In Spain, before, during and after the civil war, he used to give classes to university students and then set about cooking, washing floors, making beds and looking after the sick. "It is on my conscience—and I say it with pride—that I have dedicated many, many thousands of hours to hearing children's confessions in the slums of Madrid. They used to come with running noses. First I had to clean their noses, before beginning to clean their poor souls." These words are his and they show that he really lived the "daily smile." He also wrote, "I used to go to bed dead tired. When I was getting up in the morning, still tired, I would say to myself, 'Josemaría, before dinner you can have a little nap.' Then, when I got out onto the street, with the panorama of the day's work spread out before me, I would add, 'Josemaría, I have fooled you once again'."

His greatest achievement was, undoubtedly, the founding and directing of Opus Dei. The name came by chance. Someone once said to him, "We've got to give our all, this is a work of God." "That's the right name, ' I thought, "not my work, but God's, opus Dei." He saw this work grow before his eyes until it had spread to all continents. Then he began to travel to different countries to foment new apostolates and to give doctrinal talks to many thousands of people. The extension, number and quality of the members of Opus Dei, may have led some people to imagine that a quest for power or some iron discipline binds the member together. Actually the opposite is the case: all there is the desire for holiness and encouragement for others to become holy, but cheerfully, with a spirit of service and a great sense of freedom.

"We are ecumenical, Holy Father, but we haven't learned ecumenism from Your Holiness," Msgr. Escrivá allowed himself to say to Pope John XXIII on one occasion. Pope John laughed, because he knew that since 1950 Pope Pius XII had authorized Opus Dei to receive non-Catholics and non-Christians as cooperating associates.

Escrivá used to smoke when he was a student. But when he went to the seminary he gave his pipes and tobacco to the porter. He never smoked again. However, on the day that the first three priests of Opus Dei were ordained, he said: "I don't smoke; none of you three do either. Alvaro, you will have to take up smoking, because I don't want the others to feel that they are not free to smoke if they want to."

It happens from time to time that one of the members of the association is appointed to some important post in society. However, since the members of Opus Dei make their own free and responsible choices in everything they do, their achievements are their own affair and have nothing to do with Opus Dei. On one occasion in 1957 when an important person congratulated Msgr. Escrivá because a member of the association had been appointed a government minister in Spain, he received a rather curt reply, "What does it matter to me whether he is a minister of state or a street sweeper. What I am interested in is that he sanctify himself in his work." In that reply we have the whole of Escrivá and the spirit of Opus Dei: each person should sanctify himself in and through his work, including the government minister, if he has been put in that position. What is truly important is that he should really seek holiness. The rest matters little.