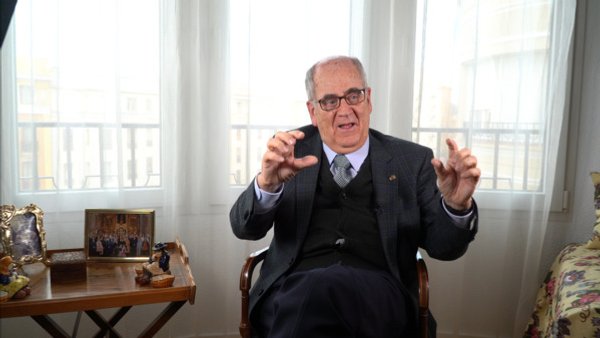

Professor Arana has over the years been a visiting professor at the University of Navarra, where he has taken part in many discussions about the compatibility between faith and reason. In the interview below, he speaks about his recent book Theology for Unbelievers, and how two years ago he finally became convinced of the truth of the Catholic faith.

How would you sum up your process of conversion?

There are many kinds of conversions, but for me two are of special significance. On the one hand, the “philosophical conversion,” which consists in a person using their natural gifts – their education, intelligence, teachers they have had or books they have read – to clarify the question of God and his existence. But one cannot say that this involves any supernatural grace, or that one has taken a step towards a religion that truly affects one’s whole life.

A second conversion is the truly religious one, which implies receiving an external grace that enables one to take the step of professing that God exists, that He has a name, Jesus Christ, and that his coming is channeled through the Catholic Church, which He founded. At times the two go together, and at times one overshadows the other

In my case, I have never been an atheist. From the age of 18 I was quite sure that, although the existence of God as a personal being could not be demonstrated like a mathematical theorem, proofs in favor of it outweighed those opposed to it. But I continued to resist a true religious conversion. On the basis of the 1968 crisis and my time spent in Madrid, I had a number of mental reservations that prevented me from saying yes, I believe 100% that that is true.”

What type of doubts did you have?

My search was intellectual. That doesn’t mean that the emotions, the sentiments, the imagination weren’t important for me, but those dimensions in my life were not so problematic. I was born into a happy family, my parents loved me, I had brothers and sisters I got on well with… In this world I have met many more good people than bad. I also met a woman, whom I came to love deeply, and we have been together for over 50 years. My failure was intellectual.

When would you say your movement towards the faith began?

I always wanted to overcome my doubts, even from the time I was young. When I turned 20 I thought the time had come to try to resolve them, since it was something central in my life. So I studied philosophy and became a professor in that discipline. And I had the good fortune of being paid for what I enjoyed doing.

And now, after 50 years, I have finally overcome my doubts and moved from incredulity to faith. In a certain way, my book is an account of that long process. not of someone who denies the faith, but someone who lacks deep feelings about the faith because of their doubts, and who has to consider ever possible aspect before finally making up their mind. Not in order to be 100% sure, because such sureness doesn’t exist, especially in questions that are really important. But, yes, enough sureness to take on the identity of a believer.

Like a person who suddenly has the premonition that a particular number is going to come up in the lottery and is ready to bet everything he has on it. Until one is able to take that step of wagering everything on a specific number, in this case on God through Jesus Christ and through the Catholic Church, one cannot say that one is a believer 100%. I finally took that step only two years ago, and from then on I am reaping the fruits of a whole life of work, doubts, sufferings, and also of joys.

Do you think your book will be of help to those who don’t believe?

It is very difficult to generalize. Just as there are many types of believers, there are also many types of atheists, doubters, and agnostics. It seems to me it is very difficult, I would say impossible, to give a formula that would be useful for all of them. I have worked practically all my life in a public university, and in a discipline, that of philosophy, where most of the people are unbelievers.

We all have our doubts, our hopes and, in some way, our faith. Each one needs to seek the certainties required to live a life with any meaning. The search of a doubter is the search for a meaning he hasn’t found yet, but which he at least has the hope of finding. I would say to any doubter or atheist, that he shouldn’t renounce the hopes he already has in his life, and that in the end things are not so dark or pessimistic as it might seem in the darkest moments.

Nietzsche, Marx... Many people claim that belief in God is merely a way to find hope in facing one’s fears and sufferings in this life. What would your answer be to this?

In the philosophy of the last two centuries, the dominant attitude has favored atheism, or at least an attitude of doubt, of skepticism. It has even given rise to what we might call the “philosophy of suspicion,” which places any presumed truth or affirmation in parenthesis.

I personally think that the critical attitude, in a certain sense, is good, since one needs to be able to evaluate whether a statement is based on sound reasons or pseudo reasons. One cannot automatically say: “I systematically deny everything presented to me.” There is a whole hierarchy of suspicions and affirmations.

I am of the opinion that what is interesting in philosophy is not the attitude of requiring that everything be absolutely clear and sure to me, but that I be a person capable of wagering. And I am going to bet my life strongly on what I see as most probably true.

What I would criticize is the attitude of saying “no” right away. It is better to be willing to see if what is presented to me as truth resists my doubts and inquiries. When someone honestly holds the attitude of trying to be somewhat neutral, in the end one begins to realize that things are not so “fossilized” as might seem, and that one needs to consider all the pros and cons carefully.