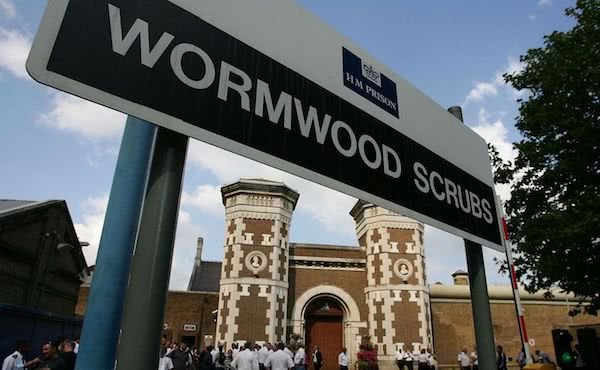

Wormwood Scrubs is a Category B prison in west London for adult males, originally set up towards the end of the 19th century. In 1979 prisoners staged a rooftop protest which led to sixty inmates and several prison officers being injured. In the 1990s, a police investigation into allegations of staff brutality resulted in the suspension of 27 prison officers. Although a 2004 report said that the situation had greatly improved after some fundamental changes, by 2008 another report stated that conditions had deteriorated and in 2014 the Inspectorate was very critical of the prison.

I contacted the prison chaplain about attending Mass there once a month with some friends, and we agreed to meet at the prison gate at 10 am one Sunday morning, half an hour before Mass was due to begin, complete with passports and other proofs of address. I was apprehensive at first, not quite knowing what to expect, but determined to go ahead regardless, inspired by Pope Francis’ example and his encouragement to be near the poor and sick, not to be afraid of ‘the smell of the sheep’.

I could not help but look around me at this other world as it unfolded: the heavy iron doors, the barking of the dogs, the filth and litter that had gathered under the cell windows, the warning signs not to approach the feral cats, the high barbed wired walls, the loud voices as prisoners tried to converse with one another through the open windows from one cell to another.

Then, suddenly, right in the very centre of the prison, we were lead into a magnificent, spacious, beautiful chapel. The contrast could not have been greater; an oasis of hope and beauty. I found out that the chapel had been completed at the end of the 19th century using convict labour. In fact, some of the prisoners had painted the gospel scenes that were behind the altar. It is said that they used each other’s’ faces to paint the apostles and that the face of Pontius Pilate bore an uncanny resemblance to the prison governor of the time!

Prisoners entered in groups from the various wings. We welcomed them in, offered a few words of encouragement, shook their hands, I also gave out some prayer cards to St Josemaría Escrivá, the founder of Opus Dei. The Mass started. The priest told them about the Year of Mercy, the most relevant part being this extract from a letter of Pope Francis about the indulgences available during the year.

My thoughts also turn to those incarcerated, whose freedom is limited. The Jubilee Year has always constituted an opportunity for great amnesty, which is intended to include the many people who, despite deserving punishment, have become conscious of the injustice they worked and sincerely wish to re-enter society and make their honest contribution to it. May they all be touched in a tangible way by the mercy of the Father who wants to be close to those who have the greatest need of his forgiveness. They may obtain the Indulgence in the chapels of the prisons. May the gesture of directing their thought and prayer to the Father each time they cross the threshold of their cell signify for them their passage through the Holy Door, because the mercy of God is able to transform hearts, and is also able to transform bars into an experience of freedom.

There were about 150 inmates there that morning out of a total prison population of about 1300. In many ways they were not so different from any other congregation; there were many who were very devout, others were more distracted and had to be encouraged to follow the Mass more attentively. Generally, they would oblige. It reminded me of being a teacher, overseeing pupils in Mass in a rough school. Some were clearly moved and tearful, perhaps on hearing the same hymns that once they had sung as children before things had started to go wrong in their lives.

Sometimes one has to persevere to do good; after only a few visits, due to high and growing levels of corruption, security became much tighter. Volunteers were no longer allowed to enter the prison without going through an extremely bureaucratic and stringent vetting process together plus some training. I decided that I would try my best to get past these obstacles. It took me over a year but by July 2017 I had been fully vetted and trained. I now have the advantage of being able to go in and out of the prison whenever I want to and I continue to attend Sunday morning Mass there at least once a month.

Little by little I got to know some of the prisoners. There is always work to be done at the end of Mass, being asked for all sorts of things, from rosaries to copies of the Bible in Vietnamese or a request that a priest visit their cell to hear their confession.

I was particularly moved by Juan from Colombia. He spoke no English but we were able to converse in Spanish. I could scarcely believe my ears as he told his story. He had been admitted to the prison about a month previously and routine medical tests had shown that he had advanced cancer. Doctors expected him only to live for a few more months. I assured him of my prayers. I was really taken by his calmness and trust. He was shortly moved somewhere else and I have heard nothing since.

One morning, one of the inmates approached me and said “You’re from Opus Dei, aren’t you?” I replied that indeed I was and asked him how he knew. He said that he had seen me giving out prayer cards of the founder. Then, out of the blue he asked why it was that St Josemaría called Alvaro ‘Saxum’? I gave him a brief explanation but I was more intrigued as to how he knew all this. He said that he got moved around a bit from one prison to another but that when he had been in Yorkshire he used to get copies of the Newsletter of Mgr. Josemaría Escrivá, a regular publication produced while his process of canonisation was on-going. He said he had never read any works of St Josemaría but that he would like to read Christ is passing by. Last Sunday I handed him a copy.

Now, when I leave the prison after Mass, as I ride my bike along the river Thames and then up to and over Wimbledon Common back home, with the fresh early Sunday afternoon air, my thoughts always go back to the prisoners in their cells and I begin to pray for them. The week of work ahead does not seem so bad now and it helps me to offer it all up for the many needs of others and to try to complain much less.

Mark Stables is a school master, married with two children