It was a habit for Josemaría Escrivá to walk with his brother Santiago, 17 years his junior, down by the park to buy from a candy vendor. One day, as they approached the stand, a gust of air blew, sullying all the candy. Then the vendor started licking off the grit from all his lollipops.

Josemaría never bought candy from him since.

This anecdote might seem like a trifle. But seen in the context of the life of a saint, it takes on a deeper meaning.

I first heard this detail about St. Josemaría, founder of Opus Dei and canonized on Oct. 6, 2002 by Pope John Paul II, from my philosophy teacher one stuffy afternoon. I doubt if she was making some metaphysical point. St. Josemaría isn't even the center of the story. Put in another protagonist and it would not have made a difference.

But maybe that's just the point: Stories about saints don't have to be the miraculous or the devastating type. Saints have always been placed on pedestals that it becomes so hard to think of them as living the same lives as we regular folk live. It also becomes so hard to think of us being like them.

This must be why St. Josemaría struck many as being revolutionary. His teaching and his own life dispelled the myth that sainthood takes you away from what is normal; that it transforms you into some superhero exempt from any kind of emotion.

Sanctity in the ordinary-this was the essence of the saint's message, from the time his own vocation began. St. Josemaría lived and grew up wanting to be an architect. This all changed, however, when one winter morning, he saw bare footprints on the snow made by a discalced Carmelite monk, presumably as some form of sacrifice. Witnessing the Carmelite monk's devotion to his calling, Josemaría realized and accepted that his life was meant for something else.

Founding Opus Dei

He became a priest on March 28, 1925 in Saragossa, and three years after on Oct. 2, he "saw" Opus Dei. It's Latin for "Work of God." In Dennis M. Helming's "Footprints in the Snow," St. Josemaría says, "the easiest way to understand Opus Dei... is to consider the life of early Christians. They lived their Christian vocation seriously, seeking earnestly the holiness to which they have been called by their baptism. Externally they did nothing to distinguish themselves from their fellow citizens. The members of Opus Dei are ordinary people. They work like everyone else and live in the midst of the world just as they did before they joined. There is nothing false or artificial about their behavior. They live like any other Christian citizen who wants to respond fully to the demands of his faith."

Opus Dei survived the civil war in Spain and spread across the globe, serving the Church in union with the Pope and the bishops. So somehow, St. Josemaría did become an architect-helping people construct the edifice of their sanctity.

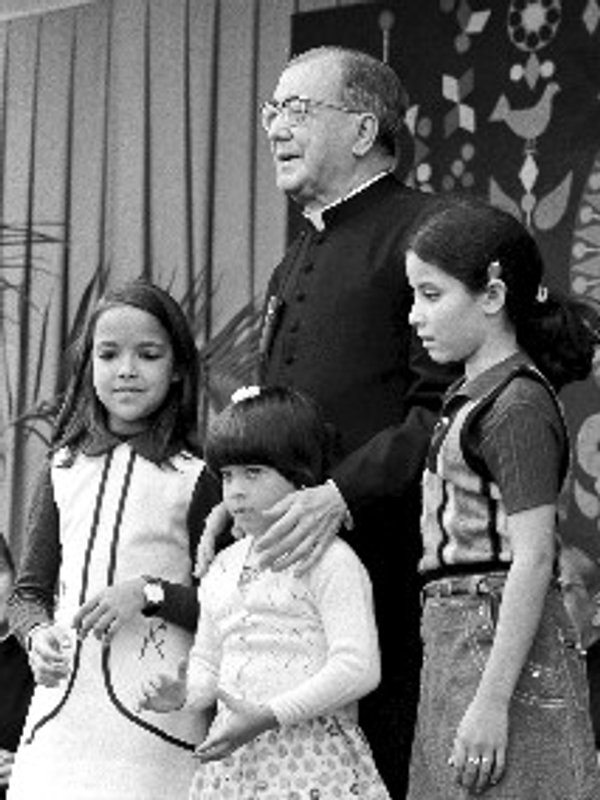

St. Josemaría died in Rome on June 26, 1975, but he and his message of sanctity in the ordinary are immortalized in the hearts of many and in that little sepia prayer card.

When I was younger, I used to call it the wishing card, a genie without the lamp and the three-wish limit. The card was pocketsize, ready to be whipped out when trouble appears.

I don't go to centers regularly. I tune out during meditations and prayers because my attention span is that of a two-year-old. I am not a member of Opus Dei. That's okay. It's either you are meant for it or not. St. Josemaría's sister, Carmen, wasn't a member either. But that didn't stop her from helping out Opus Dei. Not all are called to Opus Dei. But all are called to be good. Good enough to be saints. We're all meant for that. Even if the Big Eye in the Sky doesn't tell us so, we know we're meant for that. We are all meant to struggle every day through our ordinary ways, extraordinarily. And this is what St. Josemaría did.

So now I grapple with the ruts and bumps of life with my sepia card, reminding me that anything as lowly as getting dirty to replace a flat tire can be something wonderful in eternity.