This study published in no. 52 of of the journal Romana, it focuses on some aspects of St. Josemaría’s teachings on forgiveness and their relevance in fostering a peaceful co-existence. Because of its length, it will be published in two parts. The founder of Opus Dei invites us to rediscover forgiveness and to learn how to love: to love God and, through him, our neighbor, also when we are offended.

The words and example of St. Josemaría help us to go deeper into the beauty of forgiveness and to learn to exercise it. In the second part of the study, we will look at the meaning that St. Josemaría found behind misunderstanding and injustice, expressed so forcefully in the homily “Christian Respect for Persons and their Freedom.” We will also consider his habitual attitude in the face of offenses, and end with a reference to the practice of forgiveness in contemporary society and its concern to foster a culture of peace.

1. Rediscovering the “liberating newness” of forgiveness

Christ’s message about forgiveness was revolutionary in his time and continues being so today. It brought a complete change to the old paradigm of an eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth. The Christian message, by grounding human relationships on love, taught that forgiveness, like the love of God from which it arises, does not have any measure or limit. How should we forgive? As God has forgiven us. How many times should we forgive? “As many as seven times? I do not say to you seven times, but seventy times seven.” Whom must we forgive? All men and women, since Jesus’ command “love your neighbor” broadened the scope and embraced everyone, including one’s enemies and any offensive act. The law of vengeance was transmuted into the “logic of love.”

Christ’s message about forgiveness was revolutionary in his time and continues being so today. It brought a complete change to the old paradigm of an eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth.

Mercy and forgiveness are proclaimed in the Sermon on the Mount; this is “so important that it is the only [petition] to which the Lord returns and which he develops explicitly.” It is also emphasized in the Our Father. It lies at the core of Jesus’ message, sealed by one of his last acts on earth, when he forgave the violent death to which he was condemned.

We need to forgive because God forgave us first. We have to love “as he loved us.” “God’s forgiveness becomes in our hearts an inexhaustible source of forgiveness in our relationships with one another.” As God forgave me from the cross, with a Love that reaches the “limits of love,” so we have to forgive, going right to the furthest limit.

Forgiveness is part of divine mercy and, as St. John Chrysostom says, “nothing makes us resemble God so much as always being ready to forgive.” Therefore whoever forgives reflects God’s image with greater clarity.

To forgive is to reply with good after receiving an evil. It is an especially intense giving of oneself, which ennobles the human person. Forgiveness does not leave things as they were before, but rather renews the relationship, purifying and deepening it. Thus Christ’s death on the cross renews and elevates God’s relationship with mankind and of men and women with one another. Between the cross and the resurrection came forgiveness.

In every offense we are attacked by an evil that could give birth to another evil within us. Indeed, this is the evil that everyone has to overcome. Forgiveness prevents revenge, calms the feelings, and purifies the memory. On the part of the one who is forgiven, forgiveness enables that person to overcome both the offense committed as well as the co-responsibility for the new sin that could arise in the person offended.

The willingness to forgive protects both truth and justice, the “prerequisites for forgiveness.” It opens the path to healing wounds and makes reconciliation possible. To construct a truly human society, we need to recover the true nature of forgiveness.

This is a great challenge, since some cultures have not yet received the message of forgiveness, and there are post-Christian societies around us in which the true features of forgiveness have become blurred, reduced to a superficial religious sentiment. Moreover, to forgive others can be difficult and at times might even seem impossible. Nevertheless, “no community can survive without forgiveness.”

It seems as though today, two thousand years after Christ came into the world, just as he said about marriage, he is telling us: “from the beginning it was not so.” In a world ravaged by conflicts, human beings are capable of more; their dignity as children of God requires overcoming the recourse to vengeance, resentment and hate. The gift of self should also lead to restoring the human relationships that have been broken or undermined.

Nevertheless, since the nineties of the last century a new interest in forgiveness has arisen, a rediscovery of its importance. This has largely been the result of the scars left by the armed conflicts, terrorism, and violations of human dignity that have occurred during recent decades. The violence has in many cases ceased, but not its effects.

Governments, international organizations and local communities have tried to repair the damage by recourse to judicial actions, principally condemnations and economic reparations. But it was soon realized that to truly cure the damage caused the responses have to reach the deepest level of the human person—the same level that the offense reached, namely the radical dignity of every human being. It is impossible to reach the deepest level of the person only with these measures, which are often centered more on the offender and the state’s social order than on the person offended, and which may also be insufficient since the offenses one is confronting may be irreparable.

In a world ravaged by conflicts, human beings are capable of more; their dignity as children of God requires overcoming the recourse to vengeance, resentment and hate. The gift of self should also lead to restoring the human relationships that have been broken or undermined.

Therefore the actions of the judicial system, although necessary, are not enough, nor are financial reparations. The realization of this insufficiency has led in recent years to an important evolution of the right to reparation in the area of human rights. This evolution consists, among other aspects, in trying to ensure that the reparations offer global responses to the damage caused, including, in addition to economic losses, others of a different nature and scope.

This new approach involves concepts such as recognition, truth, repentance, personal transformation, restoration of dignity, remembering, overcoming sorrow, the need for liberation from guilt and from the desire for revenge, from hatred, etc. These elements transcend the boundaries of human justice, and lead one by the hand, as it were, to forgiveness, forgotten up until that moment, when not undervalued because of its religious dimension.

By this unexpected route, forgiveness and its curative and “liberating and newness” has become the focus of new studies which consider it from the psychological, anthropological, religious, or sociological point of view. In these works, forgiveness is seen as the solution not only for world-shaking conflicts, but also as a recourse for resolving everyday conflicts. “Asking for and offering forgiveness is a path that accords very well with human dignity, and at times it is the only path for resolving situations scarred by old and violent hatreds.”

It is in this context that we will consider the figure of St. Josemaría as a man who knew how to forgive. How he viewed forgiveness and how he lived it present us with guidelines that can serve as a framework for the present study.

In first place, our attention will be drawn to the charity that he lived to a heroic degree. Second, we will consider the message of the universal call to holiness, especially the tie between a lay mentality, freedom, understanding and forgiveness. In third place, the attacks against his person that he suffered during his life, principally in the form of calumnies and misunderstandings. Here we will look at some aspects of the homily “Christian Respect for Persons and their Freedom,” which has some of his most extensive considerations on the question of misunderstandings and injustices among men. Then, taking up some testimonies of those who knew him, we will consider the attitudes he adopted towards those offenses.

He was also a man who was attentive to the historical, cultural, and intellectual currents of the twentieth century, and found himself immersed in the passions unleashed by the Spanish Civil War. To analyze the period of that conflict would go beyond the purpose of our study, as would the overall context of his life in the twentieth century as an epoch of armed conflicts and violence. But we do want to highlight the heroic consistency of his charity in always seeking forgiveness and reconciliation among men, no matter how extraordinary the situation.

We will end the study with a look at the practice of forgiveness in contemporary society and the “culture of peace.”

2. The Great Love

a) Drowning evil in an abundance of good

This new approach involves concepts such as recognition, truth, repentance, personal transformation, restoration of dignity, remembering, overcoming sorrow, the need for liberation from guilt and from the desire for revenge, from hatred, etc.

The deepest root of St. Josemaría’s ability to forgive has to be sought in his love for God. Having interiorized the double precept of charity, he loved God above all things and therefore also his fellow men and women in a true and practical way.

In 1957, in a conversation with one of his spiritual sons, he referred to the double commandment and its internal consistency: “It seems as though I can hear someone saying: loving God above all things is easy, but loving one’s neighbor, friends and enemies…. That’s really difficult! If you truly love God ‘ex toto corde tuo, ex tota anima tua, et ex tota fortitudine tua,’ with all your heart, with all your mind, and with all your strength (Deut 6:5), then the love for your neighbor that you find so difficult will be a consequence of the Great Love; and you won’t feel yourself an enemy of anyone.”

He sensed very deeply God’s love for him and how he had forgiven him throughout his whole life. This led him to deep gratitude and to identification with Christ in loving everyone above any other consideration, overturning any barriers with the force of his affection.

He transmitted around him an atmosphere of love, valuing each person as a child of God, as the bearer of a “core” of dignity that not even sin can erase. He knew how to focus on the positive qualities in each person. He had a great dislike for any partiality towards persons, and never allowed himself to look down on others.

Thus he viewed forgiveness as a consequence of charity rather than as an added duty, going so far as to say that “I haven’t had to learn how to forgive, because our Lord has taught me how to love.” He saw charity as the source of forgiveness and forgiveness as a form of love. Perhaps the deepest form, since sometimes it can be the most difficult one to carry out. But so great was his charity that he didn’t need to forgive because he didn’t consider himself offended. He recognized and was saddened by the evil present in the offense, as a sin against God. As a man with a heart he also “felt” it, but charity from the first moment annulled any rancor, hatred, or revenge.

He followed the counsel of St. Paul: “Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good,” which he paraphrased in this way: “Let us drown evil in an abundance of good.”

b) The home that I have seen

The first place where Josemaría experienced forgiveness granted and bestowed was in his family, the home where he grew up. His parents, don José and doña Dolores, formed a Christian home where forgiveness was an integral and natural part. His family was for him a school of forgiveness and mercy, where he learned how to forgive.Josemaría as a child witnessed how his parents forgave grave injustices—a forgiveness granted with naturalness and discretion. His parents strove never to speak about unjust deeds before their children, so as to prevent any lack of charity towards those responsible.

Through his parents’ example, he learned to live a charity that went beyond justice, a special openness of heart towards the most needy, and a readiness to ask others for forgiveness and to grant it, always doing so in a discreet way.

St. Josemaría was also quick to “ask for forgiveness” and rectify if he had offended someone. Bishop Alvaro del Portillo, his closest collaborator for almost forty years, recalled that when he made a mistake “he immediately rectified the matter and, when this was called for, apologized

c. Unity of life

Closely linked to charity is one of the key concepts of his spiritual teaching: unity of life. He reminded all Christians that love for God makes it possible to unify every aspect of our life, that we cannot allow any divorce between our faith and our daily life. St. Josemaría warned of the danger “of living a kind of double life. On one side, an interior life, a life of relation with God; and on the other, a separate and distinct professional, social and family life, full of small earthly realities.”

Applied to forgiveness this means that we have to put into practice what the Catechism calls “unity of forgiveness,” since “love, like the Body of Christ, is indivisible; we cannot love the God we cannot see if we do not love the brother or sister we do see.” The Our Father highlights the importance of forgiveness, first in our relationship with God and then with other men and women.

Unity of life applied to forgiveness has many consequences. We will refer to some that seem most relevant in regard to St. Josemaría.

The first is that he forgave everyone and lived this demand in its most heroic form, forgiving even his enemies. Forgiveness of one’s enemies is especially difficult, because of the passions involved and the lack of human strength to do so, and thus the need to ground it on charity. St. Josemaría carried the commandment of love further, so to speak, than forgiveness, for he always said that he did not have enemies, that he did not feel animosity towards anyone. In his ability to forgive we see his desire, not only to overcome any negative reaction at being offended, but to reach the heart of the offending person and convert him.

He did not consider as enemies those who attacked him; nor, in the context of daily life, those who were far from him in their beliefs, their way of thinking and acting, their political or social opinions, etc. These questions can frequently lead to a distancing and even a rupture between people, both in families and in society. In this second sense, one can have more enemies than it seems at first sight; or, at least, if not enemies, people towards whom one is indifferent or even shows disdain for when, consciously or unconsciously, one falls into discrimination and refuses to accept certain persons or groups of persons.

St. Josemaría was also quick to “ask for forgiveness” and rectify if he had offended someone. Bishop Alvaro del Portillo, his closest collaborator for almost forty years, recalled that when he made a mistake “he immediately rectified the matter and, when this was called for, apologized... The quickness with which he made amends was truly remarkable, and he did not hesitate to do so in public if he felt that was called for. This was an outstanding characteristic of his behavior. And it was his desire that everyone should experience this ‘joy of making amends’.”

He never used his authority as founder as an excuse to not ask for forgiveness; moreover, he realized that precisely because of his authority he should be more attentive to doing so. In line with his message of seeking sanctity in ordinary things, he would also ask pardon for small offenses, mistakes, or misunderstandings that could arise in the life of someone with authority over others, who had to work with many people and make decisions in regard to formation and the development of Opus Dei.

Another expression of unity is thatSt. Josemaría asked the faithful of the Work and those who drew close to the apostolates of Opus Dei to do likewise. He never lowered the goal: everyone had to learn to forgive and to ask for forgiveness, doing so for love of God.

The “unity of forgiveness” is also seen in the close relationship between our being forgiven and the growth of our own readiness to forgive. A person who is forgiven is more readily disposed to forgive others. When God pardons us, our love for him grows and we see more clearly the need to forgive others. And when we forgive others, we come to realize that we too need forgiveness, and our self-knowledge grows. The “unity of forgiveness” helps to heal all human relationships. The one who always forgives finds his own readiness to forgive strengthened; he comes to know himself better, has more control over his own weaknesses and learns to understand those of others.

Forgiving is one of the areas where the breakdown of unity of life among Christians is shown most clearly. The absence of forgiveness, or a forgiveness filtered by discrimination, is a symptom of paganization, of a lack of love of God, a thermometer of weakness in Christian life. Therefore, in trying to make the true face of God known, perhaps today more than ever we need to be aware of the great evangelizing force found in the testimony of forgiveness.

Forgiving is one of the areas where the breakdown of unity of life among Christians is shown most clearly. The absence of forgiveness, or a forgiveness filtered by discrimination, is a symptom of paganization, of a lack of love of God, a thermometer of weakness in Christian life. Therefore, in trying to make the true face of God known, perhaps today more than ever we need to be aware of the great evangelizing force found in the testimony of forgiveness.

d. A priest of Jesus Christ

St. Josemaría’s priesthood is also at the heart of his teaching and personal example about the centrality of charity and forgiveness in Christian life.

Among other aspects that could be considered here, we will mention two. The first is expressed clearly in one of his homilies: “What is the identity of the priest? That of Christ.” And in his identity with Christ, a priest, who has been ordained to serve everyone, has to open his arms wide to all humanity, loving, understanding and forgiving everyone. “Neither on the right nor on the left nor in the center. As a priest I strive to be with Christ. Both of his arms—not just one—were outstretched on the Cross. I freely take from every group whatever seems to me good and helps me to keep my heart and my two arms open to all mankind.” The growth of this identification in his priestly soul is the source and the ultimate reason for his love for others and the reason why all who came to him found a merciful welcome and the strength they needed.

The second aspect is his love for the sacrament of reconciliation, both for administering it and receiving it. As Bishop Del Portillo wrote: “He had a real passion for administering the sacrament of penance... He preached incessantly on this sacrament.” He heard the confessions of thousands of people during his lifetime, and he himself went to confession each week. He insisted that priests should go to confession frequently and dedicate time to administering the sacrament of forgiveness.

The priest asks pardon from God for his own sins in confession; and he forgives in the name of Christ the sins of others when he administers the sacrament of forgiveness. He also needs to ask for forgiveness from others if he has offended them and to grant it if they have offended him. The priest is an “expert in forgiveness,” and is the human being who touches most closely both the mercy of God and human weakness. This closeness shapes the heart and soul of the priest, configuring it to “a God who forgives.”

In conclusion we can say that St. Josemaría saw clearly, and always made it a reality in his own life, that the identity of the priestly ministry was based on two characteristics: love for the Mass and for the sacrament of forgiveness. Christ is nailed to the cross and from there, as fruit of his sacrifice, he forgives. In the Mass a priest is identified with Christ whose arms are open wide to all mankind and, in administering forgiveness, with Christ who forgives from the cross.

3. At the hear of his foundational message

a. A message of love and peace

The third area where we can find clear features of forgiveness and understanding is in the foundational message of Opus Dei itself. We see an example of this in the following words:

“The Work of God has come to spread through the whole world the message of love and peace that the Lord has bequeathed to us, to invite all human beings to respect human rights... I see the Work projected through the centuries, ever young, elegant, attractive, and fruitful, defending the peace of Christ, so that everyone can possess it.”

In his writings and preaching, he stressed the dignity and equality of every human being, along with peace, reconciliation, forgiveness, understanding, coexistence, love of freedom, and freedom of consciences, rejecting any use of violence to try to win over others.

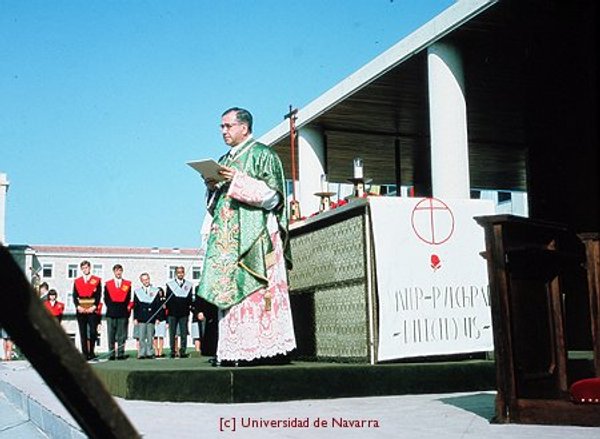

In a homily given in 1967 on the campus of the University of Navarra, St. Josemaría said:“A Christian ‘lay outlook’ of this sort will enable you to flee from all intolerance, from all fanaticism. To put it in a positive way, it will help you to live in peace with all your fellow citizens, and to promote this understanding and harmony in all spheres of social life. I know I have no need to remind you of what I have been repeating for so many years. This doctrine of civic freedom, of understanding, of living together in harmony, forms a very important part of the message of Opus Dei.”

b. Lay mentality and the rejection of fanaticism

In the text just cited, St. Josemaría links lay mentality (that is to say, the mentality of the ordinary Christian who follows Christ in the midst of everyday activities) to freedom, harmony, and the rejection of fanaticism. Intolerance is an affliction we also suffer from today, and whose influence makes itself felt in the areas of politics, culture, religion, etc. Its effects sow the seeds of violence and damage freedom and the ability to live in harmony.

St. Josemaría summed up lay mentality in three conclusions, which offer the Christian a framework for acting in civil life and which lead: “to being sufficiently honest, so as to shoulder one’s own personal responsibility; “to being sufficiently Christian, so as to respect those brothers in the Faith who, in matters of free discussion, propose solutions which differ from those which each one of us maintains; “and to being sufficiently Catholic so as not to use our Mother the Church, involving her in human factions.”

This doctrine of civic freedom, of understanding, of living together in harmony, forms a very important part of the message of Opus Dei.”

Lay mentality, grounded in one’s own freedom and that of others and in responsibility, leads to a commitment to living alongside others with harmony and understanding, and with loyalty to one’s own convictions. Living in harmony is not a matter of everyone having the same convictions or no one having any convictions. Lay mentality fosters a more peaceful culture less prone to conflicts, not by ignoring them or thinking that truth doesn’t exist, but by the way in which differences are confronted.

Lay mentality takes on even richer hues in light of the universal call to holiness, the principal message spread by St. Josemaría through Opus Dei, which points to the dignity of every man and woman, created in the image of God. Christians aware of this dignity have their heart open to everyone without discrimination of any kind. Moreover, this call is given in the middle of the world, precisely in the place where conflicts arise and where they should be resolved.

A consistently lived charity prevents Christians from falling into fanaticism towards their fellow citizens, whether or not they are brothers and sisters in the faith. “There is nothing further from the Christian faith than fanaticism—that unholy alliance of the sacred and the profane, whatever guise it takes.”

The rejection of fanaticism also means that there is no legitimate response to fanaticism with fanaticism. Trying to overcome an evil with another evil only results in continuing the cycle of revenge and violence. Vengeance is not a true solution to any problem. Evil is overcome by good, falsehood by truth. The spread of the truth has to be accompanied by charity.

At the same time, lay mentality is completely opposed to passivity or inhibition. It leads to exercising one’s rights, to fulfilling one’s civic duties, to committing oneself to the truth, to practicing one’s faith in private and in public, and to striving to transform society.

In the inevitable contrast between the action of the Christian in the world and a paganized society, there is put to the test the harmonizing of truth and charity. It is precisely there, in daily action, where Christians become aware of the importance of their evangelizing role, for they are the ones who, working with freedom and responsibility, have to fuse truth and charity in each specific case.

Jaime Cardenas del Carre

Doctor in Law (Pontifical University of the Holy Cross)