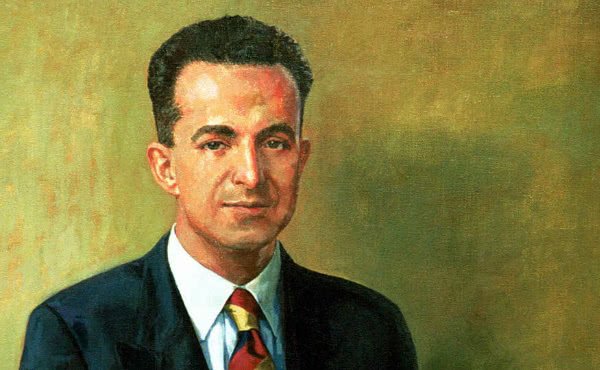

Isidoro Zorzano was born in Buenos Aires (Argentina) on September 13, 1902. He was the third of five children of Spanish immigrants. In 1905, with their economic situation in life now secure, his parents decided to return to Spain, although intending to eventually return to Argentina. The family moved to Logroño, where Isidoro did his elementary and high school studies. In 1912 his father died unexpectedly, and his mother decided to remain there.

In January 1916 he met Josemaría Escrivá, a new classmate of his who had just arrived from Barbastro. The two of them became friends. Isidoro graduated from high school in 1918 and began to prepare for the entrance exam for the Special School for Industrial Engineers in Madrid, a city to which he moved in October 1919. While still an adolescent, Isidoro intensified his religious practices and sought the help of a priest who could advise him in his Christian life. He carried out works of mercy and, as a friend of his recalled, “he was always ready to help anyone at any time.”

In 1924, with the collapse of the Spanish Bank of Rio de la Plata, the Zorzanos lost almost all their savings. Isidoro and his younger brother, Francisco, thought about giving up their studies in order to support the family with their work. Nevertheless, their mother and two sisters wanted both of them to continue their studies. Isidoro began to give private classes to bring in some income.

In June 1927, Isidoro earned the degree of industrial engineer. He started giving classes in an academy that prepared students for the entrance exam to the school of industrial engineering, and also worked briefly in the shipyards of Matagorda (Cádiz). But soon he decided to move to Malaga, to work in the Andalusian Railroads Company and to give classes in the Industrial School in that city.

At that time, Isidoro began to sense a deeper spiritual restlessness. On August 24, 1930, he had a long conversation with St. Josemaría Escrivá, his former high school classmate, who had now been a priest for five years. St. Josemaría explained to him the message of Opus Dei, founded in 1928. Its purpose was to foster the search for holiness and apostolate through professional work and the fulfillment of one’s ordinary duties. Isidoro saw at once that this ideal corresponded fully to his own aspirations and decided to join Opus Dei.

He returned to Malaga and went back to his regular routine, but now everything had taken on a new light. He deepened his life of prayer, and woke up early every day to attend Mass and receive Communion. He also was generous in assisting the poor; among other things, he dedicated many hours to giving classes to poor children in some schools run by the Adoration sisters and by the Jesuit Father José Manuel Aicardo. One of his students in the Industrial School, who also accompanied him on his excursions with the Hiking Club, recalls that he was very friendly and easy to get along with, and possessed a well-balanced temperament; he made use of every opportunity to serve others and bring them closer to God. One of his colleagues at the university, who also knew him in Malaga, recounts that although his salary enabled him to live quite comfortably, he in fact lived frugally, since he used his money to help his family and the needy.

Everyone recognized his sense of justice and his closeness to those working under his direction. He did not discriminate against anyone because of their political ideas; he was concerned about and served everyone, both in the office and at the school. His students recall that he sometimes gave special classes without charge so that everyone could learn the material and pass their exam. In 1936 a bitter anti-religious attitude began to spread and the environment in the city became very dangerous. In June, some of those under him told him that certain political groups had decided to kill him because he was a Catholic. Therefore he moved to Madrid.

A short time later the civil war broke out and, in the regions controlled by Communists and anarchists, a violent religious persecution was unleashed. St. Josemaría and the handful of young men belonging to Opus Dei had to go into hiding or were imprisoned because of their Catholic faith. Isidoro could have left Spain, but decided to remain in Madrid so as not to separate himself from the others. Relying on a precarious form of documentation — a Buenos Aires birth certificate — and knowing that his life was constantly in danger, he helped keep the members of Opus Dei united to St. Josemaría and to one another.

During those years he assisted many people not only spiritually, but also by obtaining for them provisions and food that he managed to obtain with great personal sacrifice, giving up much of what he needed for himself. He endured so many privations that once he even fainted on the street. During those months his love for the Eucharist was very evident. Despite all the restrictions, he brought St. Josemaría and some other priests the bread and wine they needed to celebrate Mass secretly. He also kept the sacred hosts in his room so that those in hiding could receive Communion, and informed those he knew of the possibility of attending the Eucharistic celebration in certain apartments.

After the war, Isidoro obtained a position in Madrid with the National Western Railroad Company. A colleague declared that “he had a great moral authority for those working under him, first because he was a person of great talent and extraordinary competence, and second because his dealings with them were so warm and fatherly that no one could resist him.” St. Josemaría appointed him administrator of the apostolic instruments of Opus Dei, a task he carried out generously and humbly, never losing his peace in confronting the constant financial difficulties in the apostolic initiatives, which always operated with a deficit.

He knew and loved Christ’s life in its every detail, and had recourse to our Lady with filial affection. His great love for God was shown in his service to others and his care for little things. A witness who knew him in Madrid wrote that he had seen “in his actions and words, and in the expressions of his soul, a marvelous way of living, with simplicity and naturalness, the heroism of an ordinary life immersed in God. When with Isidoro, I sensed God’s presence in a simple and unobtrusive way.”

At the beginning of 1943 he was diagnosed with malignant lymphoma. He accepted this painful sickness with courage and abandonment to God’s will. One of the nurses who took care of him recalled: “He never needed anything; for him everything was good and he never complained.” He died with a reputation for holiness on July 15 of that same year, at the age of 40, and was buried in the cemetery of La Almudena. One of his co-workers at the Western Railroad Company said: “When we talked about our bosses, it was common for someone to say: ‘Don Isidoro is a saint.’”

In 2009 his mortal remains were transferred to the church of St. Albert the Great in Madrid, where they now repose.

On December 21, 2016, Pope Francis instructed that the decree on the heroic virtues of Isidoro Zorzano be published and transcribed in the acts of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.