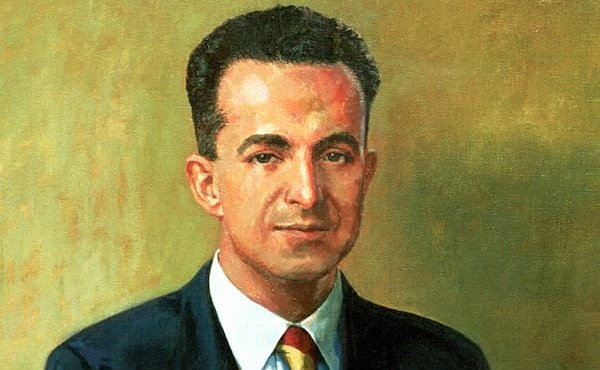

Isidoro Zorzano was the first person to join Opus Dei and persevere. He lived his vocation to Opus Dei in the unusually difficult circumstances of the Spanish Civil War and the immediate post-war years.

Early Life

Isidoro was born in Argentina in 1902, the third child of a Spanish couple who had moved there seeking a better life for themselves and their children. Although they did well financially in Argentina, when Isidoro was three they decided to return to their hometown of Logroño in northern Spain.

During his high-school years, Isidoro met and became friends with Josemaría Escrivá whose family moved to Logroño after the bankruptcy of their family business. In 1912, Isidoro’s father died. Despite this loss, the family continued to be reasonably well-off and Isidoro was able to graduate from high school and gain admission in 1921 to the highly competitive School of Industrial Engineering in Madrid.

Life changed radically for Isidoro in 1927 with the failure of the bank where most of his family’s money was deposited. From being a more or less carefree student, Isidoro suddenly found himself responsible for taking care of a financially hard-pressed family. To help make ends meet, he found a part-time job as an accountant and started walking to school rather than taking the bus.

In 1928 after graduating from engineering school, he found a job in the south of Spain, first at a shipyard in Cadiz and a few months later at the headquarters of the Andalusian Railroad in Malaga. As an industrial engineer, Isidoro had a brilliant future ahead of him, and several young women in Malaga thought he would be a good catch, but Isidoro felt that he needed to solve his family’s precarious financial situation before considering marriage. Moved by his concern to contribute to better the condition of workers, he began teaching mathematics and electricity in the evening at the Industrial School of Malaga which trained young men to become industrial technicians. He offered free tutoring sessions to students who found the material difficult.

Vocation to Opus Dei

By 1930, Isidoro had begun to feel that God was asking something more of him. In keeping with the mentality of the time, he thought this must mean joining a religious order. But somehow that did not fit with the ideal he had formed of harmonizing dedication to God, professional work, and care for his family. In August he received a note from his old friend and classmate Escrivá asking him to see him the next time he was in Madrid. Isidoro knew nothing about Opus Dei but was hopeful that Escrivá could help him see more clearly what God was asking of him.

On August 23, 1930, Zorzano took the train to Madrid where he would transfer to another train to spend his vacation near Logroño. He went to see Escrivá but found that he was not at home. Rather than going directly to his next destination, he hung around the neighborhood for a while. Meanwhile, Escrivá, who was visiting a sick person, began to feel uneasy for no apparent reason and cut his visit short. On the way home, rather than taking the most direct route, he went somewhat out of his way and ran into Zorzano on the sidewalk. Isidoro immediately told him about his concerns and they agreed to meet and talk at length that afternoon.

Isidoro explained at greater length his situation, and Escrivá told him about Opus Dei, which involved a full dedication to God without abandoning one’s profession or place in the world. Isidoro immediately joined Opus Dei. That evening he continued his trip but with a sense of peace and joy. As he wrote: “I feel completely comforted now. I find my spirit invaded by a sense of well-being and peace that I have never felt before.”

When Isidoro joined Opus Dei, he had little religious education and not much interior life. Of course, he had only the sketchiest idea about the specifics of the spirit of Opus Dei. It would have been helpful for him to be in close constant contact with the Founder, but that was not to be. For professional reasons, Isidoro would spend the next years in Malaga, and his contact with Escrivá would be limited to letters and occasional trips to Madrid. Within the limits imposed by distance, St. Josemaría took advantage of every opportunity to help Zorzano develop a more robust interior life. In a letter written in November 1930, for example, he encouraged him: “Look. To be what we and our Lord want, we have to lay the foundations before all else in prayer and expiation (sacrifice). To pray. Let me repeat, never omit your meditation when you get up. And offer every day as expiation all the annoying things and sacrifices of the day.”

At first, Isidoro received communion only on Sundays, and not every Sunday because he often organized Sunday excursions to the nearby mountains. The excursionists were able to get to Mass in nearby villages, but the schedule of the excursions combined with the rules then in effect about the eucharistic fast made it impractical to receive communion.

Initially, Isidoro seems to have focused on taking part in as many apostolic activities and social works as he could, but gradually he came to understand better the importance of mental prayer and the sacraments. By the end of 1932, he was receiving communion every day. Soon he was also giving formation and guidance to a new member of the Work, Josemaría González Barredo, who was teaching in the town of Linares, about 150 miles (250 km) away.

With the opening of the first center of Opus Dei in Madrid in 1933, the economic needs of the Work also increased. Isidoro sent to Madrid a large percentage of his salary to the point of leaving his bank account virtually empty. In March 1935, he made a permanent commitment to Opus Dei.

As Spain drew closer to civil war, the railroad shops where Isidoro worked became increasingly radicalized His fairness, sense of justice, and concern for his workers and their families won the respect and even the affection of most of the men who work under him, but his known allegiance to the Church triggered the antipathy of some Communist and Anarchist workers. One day in the shop a crude sign appeared: “Death to Isidoro.” Rather than becoming angry, he said that “we need to pardon [those who made the sign] because they don’t know what they are saying.”

During the school year 1935-36, Isidoro decided that he needed to move to Madrid so that he could receive more intense personal formation, help run the DYA Academy/Residence, and give a hand with the formation of the young members of the Work. A final reason for moving was the extremely radicalized political environment in Malaga generally and specifically in the railroad shops, which made life unpleasant and posed a real personal threat to Isidoro because the Anarchists and Communists viewed practicing Catholics as dangerous political opponents. On May 22, Isidoro requested leave from the railroad and on June 7 he arrived in Madrid. He found in the DYA Academy/Residence an environment of fraternity, work, and good humor that contrasted sharply with the climate of violence and tension in the streets. On June 17, DYA purchased a new house. Isidoro helped with the move which was completed by July 13.

The Outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

Four days later, parts of the Spanish army rose against the left-wing government. Although the authors of the uprising had in mind a quick coup, the uprising failed in most major cities and Spain soon found itself in a civil war that would last almost three years and cost 500,000 lives.

In Madrid, as in most other areas where the military uprising failed, the attempted coup triggered a political, social, and economic revolution led by Socialists, Anarchists, and Communists. The Republican government, in a desperate effort to put down the uprising, distributed arms to militia groups associated with Socialist and Anarchist trade unions. They quickly took control of the streets and the government temporarily lost all effective control. Militia groups confiscated property, ranging from factories to private automobiles, burned churches and other church property, and assassinated those they considered political enemies, including approximately 7,000 priests and religious. In Madrid, during the civil war, some 700 priests and religious were assassinated, more than 40% of the total living in the capital at the outbreak of the war. Almost all of these assassinations took place in the second half of 1936, especially in August. At that time, being a priest, or simply being known as an active Catholic meant mortal danger.

Although Isidoro was not well-known in Madrid and although his having been born in Argentina could provide him some protection, he was in real danger because left-wing workers in Malaga sent a denunciation complete with pictures to their comrades in Madrid. He decided to hide out in his family’s apartment. The Argentine embassy gave the Zorzanos a sign to put on the door of their apartment which said that it was under the protection of Argentina. This provided some degree of security. For approximately two months Isidoro stayed at home without setting foot outside.

Opus Dei’s Go-between on the Streets of War-Torn Madrid

At the end of those two months, Zorzano had lost quite a bit of weight due to the scarcity of food in Madrid. He had changed his haircut and had purchased dark prescription glasses. His appearance had changed enough that he was no longer in much danger of being recognized as the man in the picture sent from Malaga. He had obtained from the embassy a birth certificate showing that he had been born in Buenos Aires and an armband with the colors of the Argentine flag. Together they might be sufficient to convince militia patrols to let him pass, but if he were arrested they would not do him much good. For a year after he emerged from hiding, he was not able to get an Argentine passport or other document accrediting his Argentine nationality because Argentina granted such documents only to those who had done their military service in Argentina.

When he emerged from the house, Isidoro began to act as a liaison between St. Josemaría and the other members of the Work. It is clear in retrospect that by the time Isidoro began to act as liaison, the systematic execution of priests and other Catholics had largely come to an end. The danger of being imprisoned for being an active Catholic was, however, still great.

At the time, Isidoro probably thought he was in serious danger not only of being imprisoned but of losing his life. He willingly ran those risks, however, to contribute to the survival of the as-yet new-born Opus Dei by fulfilling the role of liaison given him by the founder. Escriva, for his part, does not seem to have understood how precarious Isidoro’s situation was.

During the fall of 1936, St. Josemaría hid out in a private insane asylum run by a friend. Isidoro visited him virtually every day to receive his support and guidance, to bring him wine for celebrating Mass, to keep him informed about the situation of other members of the Work, and to receive messages to pass on to them. He also began to visit frequently the members of the Work who had been imprisoned. A few mothers and wives of political prisoners visited them from time to time, but almost no men were willing to run the danger of entering a prison to visit a political prisoner. Hernández Garnica, whom Zorzano visited almost every day in prison, recalls: “At a time when no men went to visit prisoners in jail because it was too dangerous, he visited me. He came repeatedly to the San Antón prison and did all he could to get me released on grounds that I had a kidney problem.” When Hernández Garnica was transferred to a prison in Valencia, Zorzano wrote to the members of the Work there urging them to see what they could do to help him.

Isidoro went frequently to visit Hernández Garnica’s family to give them any news he had and to try to console them. Hernández Garnica’s mother says: “when we told him that he was running great risks, he said he was not afraid because he was an Argentine citizen. But we all knew that many people had lost their lives despite being foreign.”

Isidoro also visited frequently members of the Work who had sought asylum in foreign embassies. This too involved considerable risk since the militia units that guarded the embassies looked with suspicion on visitors. Vicente Rodríguez Casado had found asylum in the Norwegian Embassy. He recalls that Isidoro “talked with enormous confidence in God and with great naturalness and simplicity about what the Lord would do through the Work very soon if we were faithful. My faith grew enormously in contact with his. I had not lost my faith, thanks be to God, and I had complete security. But seeing him and hearing him, my faith, which was abstract, became concrete, and ideals became realities.” When Rodríguez Casado tried to impress upon Zorzano the danger involved in visiting the embassy so frequently, Isidoro simply “smiled and told me that if we use the means God could not fail to assist us.”

Zorzano also visited Alvaro del Portillo, the future Prelate of Opus Dei, who had found temporary refuge in the Mexican Embassy. Alvaro says: “We spent a long time talking about the things that were important to us: the situation of the Father, and that of all the rest of the members of the Work. … I recall his strikingly supernatural vision of so much tragedy, his great confidence in God, and the naturalness and simplicity with which he expressed his hope. I also recall his security that if we were faithful God would soon bring forth great fruits of salvation, of souls, and of peace through the Work. All this did me a great deal of good.”

In addition to visiting the members of the Work who were in Madrid, Zorzano tried to locate and correspond with those who were in other parts of Spain. They sent their letters to the founder to Isidoro who brought them to Escrivá. Because of censorship, all the correspondence had to be carried on in a sort of code that arose spontaneously among them. Thus, for instance, Escrivá became “the Grandfather,” the Work was “the Grandfather’s business,” Our Lord was “Don Manuel,” and the Blessed Virgin “Don Manuel’s mother.”

The Legation of Honduras

In mid-March 1937, Zorzano went with a car to the insane asylum where St. Josemaria had been hiding out with his brother Santiago. He took the two of them to the Legation of Honduras where they had found refuge with other members of the Work. Isidoro visited the legation frequently. He brought not only information about the other members of the Work but also the small amounts of food and other supplies that he could assemble. The wine he brought made it possible for Escrivá to celebrate Mass every day. Isidoro took advantage of his visits to seek advice from Escrivá and to receive assignments from him.

Isidoro’s most important function was to serve as the conduit between the Founder and the other members, who very much needed his support and encouragement. During those months, Escrivá preached meditations frequently to the members of the Work who were with him in the Legation. Immediately after each meditation, one of them wrote down as best he could the main ideas. Isidoro collected these texts which he used for his own mental prayer and made them available to the other members in Madrid. For a time, he brought the texts with him when he visited Vicente Rodríguez Casado in the Norwegian embassy, but when the militiamen who controlled access to the embassy began searching visitors more rigorously, he decided he could no longer do so. Instead memorized the texts and recited them to Vicente. He also began to share these texts with Josemaría Albareda, a soil scientist in his mid-thirties who gave signs of a possible vocation to Opus Dei.

In his letters to the members of the Work outside Madrid, he shared short texts from Escrivá. In May 1937, for instance, he passed on to Francisco Botella who was in Valencia what the Founder had written to him:

You give me the impression of being discouraged. I find that you are crestfallen, annoyed…, and tired. I can’t recognize you. If you are children, children insist stubbornly when they meet obstacles until they overcome them and encounter greater satisfaction from achieving their goals [despite the obstacles]. If you are men, men grow in the face of obstacles and smile… They convert into a manly sport what was a painful duty and always end up satisfied whether they achieve their goals (or not, which doesn’t really matter).

In June 1937, Zorzano wrote again to Botella:

My grandfather [Escrivá] never stops repeating the refrain “joy with peace.” His words seem to go straight to the heart. What we have to do is use all the means at our disposal in all of the tasks entrusted to us. Whether things turn out well or poorly is not terribly important. The outcome will always be for the best, provided that we let ourselves be guided by Don Manuel [Our Lord].

A few weeks after the founder took refuge in the Legation of Honduras, the Argentine embassy told Zorzano that since he had been born in Argentina he was eligible for evacuation from Madrid to another country. Madrid continued to be bombarded, finding food was increasingly difficult, and Zorzano continued to run the risk of being arrested and thrown in prison. The prospect of escaping from all of this was extremely attractive, but Isidoro realized that Opus Dei and its founder needed him in Madrid. He consulted Escrivá about what he should do.

Escrivá, who underestimated the dangers to which Zorzano was exposed, sketched out the advantages of staying in Madrid but encouraged Isidoro to act with “the greatest freedom.” Zorzano normally did not act without considering matters at length. In this case, however, after talking with his relatives, he decided quickly to remain in Madrid. He did not even explain to St. Josemaría that he did not have papers showing that he was an Argentine citizen and was, therefore, in greater danger of being arrested and perhaps executed than Escrivá seemed to think. St. Josemaría was overjoyed at his courage and generosity: “I did not expect less from you, Isidoro. Your decision is what Our Lord undoubtedly wants.

In early April 1937, Jiménez Vargas, a member of the Work who was serving in the Republican army, decided that Escrivá needed him in Madrid. He deserted from his brigade and went directly to Isidoro’s home. He recalls that “despite the danger to himself and his family of giving shelter to a deserter at that time, he did not show the least fear or lack of decision.” Zorzano went to Jiménez Vargas’ home to search for civilian clothes and managed to arrange for him to take refuge with Escrivá in the legation of Honduras.

During the early months of 1937, in addition to his ongoing efforts to stay in touch with the other members of the Work and to encourage them to remain faithful to their vocation, Zorzano dedicated himself to three major tasks: trying to arrange for an embassy to evacuate the members of the Work who were refugees in the Legation of Honduras; preparing the paperwork to claim from the Spanish government damages to DYA’s property; and covering the need for food and other items of the refugees in the Legation of Honduras and the families of members of the Work.

Attempt to Arrange Escape through Diplomatic Channels

Like most people, Escrivá and the other members of the Work had originally assumed that the war would be relatively short. As they saw it, the problem was simply to survive until it ended and they were able to take up once again the apostolates of Opus Dei. As 1936 gave way to 1937, however, it began to appear that the war might drag on indefinitely. Escrivá and the others became increasingly anxious to escape from Madrid and reach the Nationalist zone where they would be free to carry out openly their apostolate.

By early 1937, more than 10,000 people had found asylum in an embassy or legation in Madrid. In January and February, the Argentine embassy evacuated some 300 refugees to whom it had been granted asylum. In March, the Mexican embassy evacuated 600 persons. Between March and July 1937, several European and South American embassies succeeded in evacuating some 3,000 refugees.

During the spring of 1937, diplomatic evacuation appeared the best way for members of the Work to escape from Madrid. The most obvious course was for them to be evacuated by the legation of Honduras where they had received asylum. There were, however, serious difficulties. The head of the Honduran diplomatic mission was only an honorary counsel, and the Honduran consulate did not have the rank of an embassy but had the lesser status of a legation. More importantly, the government of Honduras had broken diplomatic relations with the Spanish Republic and recognized Franco’s government. Nonetheless, for a time the members of the Work continued to hope that the Honduran legation would be able to evacuate them. At the end of April, they learned that the Government of the Republic had refused to grant visas to the Honduran consul and his family.

Although Escrivá did not immediately give up all hope of being evacuated through the good offices of Honduras, he strongly urged Zorzano to find another solution and to find it quickly:

It is essential to keep on top of things to the very end… [because] just a delay in the paperwork can delay the success of the project, and even impede it. I think I’m speaking clearly. Don’t leave things for tomorrow. Today!!! I don’t care whether it is Chile or China! That’s all the same to me. But do something.

Working through whatever contacts he could find, Isidoro tried to interest the embassies of Chile, Turkey, Panama, and Switzerland in evacuating the members of the Work, but without success. Escrivá continued to urge him and the other members of the Work to leave no stone unturned, but he also told them: “I am very pleased with you and more pleased with the One who allows you to encounter difficulties, humiliations, and hassles. This means things are going well.”

In early June 1937, the Republican government told the diplomatic corps that in the future it would allow only women, children and the elderly to be evacuated. It was no longer possible to hope that the members of the Work in the Legation of Honduras who were of military age could escape from Madrid through some diplomatic arrangement.

Food and Supplies

As the months went by, the shortage of food and other necessities in Madrid worsened. Zorzano worked diligently to find food and distribute it to the members of the Work and their families. He received some from the members living in eastern Spain where food was more abundant. Packages also arrived from a family in the little town of Damiel, about 100 miles south of Madrid. A member of the Work in Madrid who was employed in the offices of a prison was able to buy some food in the prison’s commissary. Isidoro himself was able to purchase some items in the commissary of the Argentine embassy. For some months, he also went to militia barracks with false documents and drew rations. As the scarcity of food in Madrid increased, however, officials in the barracks began to suspect that something was wrong and arrested a friend who had helped Isidoro so he had to abandon this source.

He sent whatever he could obtain to the Legation of Honduras, to other members of the Work in Madrid, and to the families of the members of the Work in Madrid but the quantities he could assemble were pitifully inadequate. Most of the packages he received weighed only about two pounds (one kilogram). The food was elementary, mostly garbanzos and other beans, sometimes insect-infested, condensed milk, potatoes, and olive oil. Especially prized were ham and sausage, but they were rare. Nonetheless, in a city where milk, fresh vegetables, meat, and fish could be purchased only with a doctor’s prescription and where food of all kinds, including bread, was in very short supply, Isidoro’s efforts helped to lessen the threat of starvation

Reparations for Damages to DYA’s Property

Toward the end of April 1937, Escrivá learned that one of the officials of the Legation of Honduras had filed a claim against the Republican government for damage to property he owned in Madrid. Escrivá immediately thought that the not-for-profit that owned the new building of the DYA Academy/Residence should also file a claim. Isidoro was the logical person to undertake this task because he was President of the not-for-profit, was relatively free to move around Madrid, and could request the support of the Argentine embassy.

Isidoro together with Sainz de los Terreros immediately set about drafting a claim and making a list of the items that had been stolen or destroyed. It soon became clear that the Argentine embassy was not likely to do anything, among other reasons because Isidoro had not fulfilled the required military service.

Zorzano sent copies of the documents he had drafted to Pedro Casciaro in the hope that he might be able to interest the British embassy since Pedro’s grandfather was a British citizen. He also briefly considered trying to involve someone he thought was from Chile in the hopes that the Chilean embassy might support the request, but it turned out that the person had lived in Chile but was not Chilean. He tried getting a Bolivian and a Paraguayan involved, but these efforts were also in vain. Escrivá encouraged Isidoro and the others involved in the project to keep trying. Isidoro took this not simply as encouragement but as a directive he should obey, even though Escrivá indicated that he understood the efforts might fail: “Whether you achieve anything or not, what tranquility for us all to know that we have done everything possible to defend the patrimony of [the not-for-profit that owned DYA’s building.]

Failing Health

As the war dragged on, Zorzano’s health gradually deteriorated, undermined by lack of food, cold, and the many concerns that weighed upon him. Psychologically, he suffered from the tension caused by the ongoing bombardment of the city, which often caught him out in the street running errands. His determination to carry out faithfully all of the assignments Escrivá gave him also weighed on him. Many of the tasks, like arranging the evacuation of the refugees and convincing the government to pay for the damages to DYA’s building, were virtually impossible to carry out, but Isidoro suffered when his efforts failed. In a letter to Casciaro in June, he commented, “Recently we don’t succeed at anything. If we are asked to take care of something, it turns out that we fail.”

By late summer 1937 Isidoro was down to approximately 105 pounds (48 Kg). He was so weak that after walking a short distance he had to sit on a bench to regain his strength. He attributed his ability to keep going forward despite all these difficulties to the Eucharist. Most days he was able to attend Mass in a nearby apartment. At the end of Mass, the priest gave him consecrated hosts so that he could distribute Communion to other people and receive himself if the next day he could not make it to Mass. He noted in his diary: “It is something very impressive to carry Our Lord, to be converted into a monstrance. It is a magnificent way of being constantly aware of his presence because of the precautions that you have to take to carry him with the dignity the King of Kings merits.”

Director of Opus Dei in Madrid

Isidoro learned that in Barcelona it was possible to engage men who had been smugglers in peacetime to guide a group across the Pyrenees mountains into France. From there, it would be easy to cross back into the Nationalist-controlled part of Spain. The trek through the mountains would be arduous and anyone caught in the attempt would be executed, but it seemed the best available option. By the end of September, preparations were complete. Escrivá, six members of the Work, and Tomas Alvira, who would eventually become the first married member, made their way to Barcelona, established contact with a smuggler, and finally made their way through the Pyrenees mountains into France and from there into the Nationalist zone of Spain. Zorzano stayed behind in Madrid as the director of the eight members who for one reason or another remained in the Republican zone.

Isidoro worked diligently to alleviate the isolation of the members of the Work stuck in the Republican zone. He frequently visited those whom he could, wrote to the others, and encouraged them to write to each other. For a time, he visited every day those who were living in Madrid because “we feel more and more each day the need for this union to cure the deficiencies of the isolated life we have lived until a short time ago.” During these visits, they talked primarily about the Work. “We are so concerned about it that we barely talk about the events of the war.”

Isidoro transmitted to others, and particularly to other members of the Work his sense of prayer. He wrote to Botella for instance: “Now that we face so many difficulties, we should spend more time with D. Manuel [Jesus] and tell him about absolutely all our little things. We should make him our confidant and demonstrate to him, in every way that we can, our love and affection.” As a way of promoting a sense of unity among the members of the Work, Isidoro suggested: “Although we are separated we can do something together that will unite us more, namely we can all recite the Preces [brief prayers composed by St. José Maria and recited daily by members of the Work] at a fixed time, for example, eight in the evening. What do you think? United, not in a single place, but by the same spirit.”

The three members of the Work who had remained in the legation of Honduras because it would be too dangerous for them to emerge began to press Isidoro to allow them to enlist in the Republican Army and attempt to cross the front lines to the Nationalist zone. Isidoro stoutly rejected their requests, stressing “the advantage of waiting without exposing yourselves to dangerous adventures in which the risk is extraordinarily high and the possibility of success merely hypothetical.” In response to their insistence that they needed to get to a place where they would be free to do the apostolate of Opus Dei, he responded, “Are you sure that you are less useful where you are?”

In mid-June, 1938 the refugees insisted again even though they had recently learned that someone who had left the Honduran consulate, enlisted in the Republican Army, and tried to cross the lines had been killed in the attempt. They were astounded when Isidoro responded, “With the help of Don Manuel [Our Lord] I have thought carefully about your projects. […] I think that you can carry them out and that Don Manuel and Doña Maria [the Blessed Virgin] will answer your desires, which we share.”

What the refugees did not know, and what Isidoro did not reveal until he was on his deathbed, was that praying before a crucifix he had received from our Lord the assurance that the project would be successful and had even learned the date on which they would cross the lines. (Escrivá had also learned in prayer the date of their arrival.)

Between when they left the legation of Honduras and when the Republican army shipped them out to the front, the former refugees spent several months in Madrid. During that time, they were in constant contact with Isidoro. According to Del Portillo:

whenever possible we went to his house or we got together in a boardinghouse on Goya street and there made our prayer and talked about the things of our family. During those months, Isidoro did us a great deal of good with his conversation, with all his dealings with us, and above all with his example. His spirits were always the same. He always had the same confidence in God and the Work. And he always had a cheerful gravity and naturalness.

Many days they went together to the barracks to which the three former refugees had been assigned by the Army. They sat on the ground to share the scarce rations they were given and talk. On feast days of the Blessed Virgin they celebrated by “following the Father’s custom of giving something to the poor on her feast days; we distributed the rations to the poor.”

One day after eating they began commenting about the disasters and advantages of the war.

Isidoro began to draw up a list of the good things that the war had brought us and was bringing us. He saw it in a completely supernatural way, as a magnificent opportunity that God was providing us to sanctify ourselves. Full of joy he enumerated the virtues -- above all, charity and fraternal union-- that under those circumstances and through the grace of God we were growing in. I recall that when we got home we were full of joy and interiorly gave thanks with our whole heart to God for all the gifts he was giving us.

The End of the Civil War

By the beginning of 1939, it was becoming obvious that the war would soon end with a Nationalist victory. The major question was whether the Republic could negotiate some type of agreement or would be forced to surrender unconditionally. In early 1939, the government of the Republic arrested a hundred young Spanish men who were also citizens of other countries on grounds that they were simply trying to avoid military service. Isidoro was among those picked up. He was held for a day before being instructed to go every day to have his passport stamped. For five days in mid-January, he took refuge in the Argentine embassy. When he left, embassy personnel threatened to withdraw Argentina’s protection if he insisted on remaining in Madrid. Isidoro, however, knew that he was needed there by his own family, by the members of the work, by the families of the members, and by friends. He decided to remain.

At the end of March 1939, heavy fighting broke out between Republican forces that wanted to surrender and those that wanted to continue fighting. This further weakened the Republic, and on March 28 Nationalist troops occupied Madrid. It was the end of a 982-day nightmare during which Isidoro risked his life in the service of others. They had been days of isolation and of hunger in which he sowed serenity and good humor despite the lack of any natural reason to be cheerful. His recourse to our Lord and our Lady, and his loyalty to Escrivá had maintained him.

Working for the Railroad and as Administrator of Opus Dei

At the end of the Civil War, Isidoro went back to work for the railroad as head of the Office of Research on Rolling Stock and Locomotives, but based in Madrid, not Malaga. He worked there until the fall of 1942 when illness forced him to retire.

Isidoro had learned from St. Josemaría the importance of doing his work well as an offering to God. One of his colleagues at the railroad recalls that he “always stood out for the exemplary way in which he fulfilled all his duties, even in little things, because nothing that he needed to do seemed to him of little importance.” He was among the first to arrive at the office and rarely took off time at midmorning, as did most of his colleagues, to go to the bar for a cup of coffee or a beer.

His immediate supervisor was ill-tempered and hard to get along with, but Isidoro accepted with a smile his outbursts. He was not, however, afraid to defend his subordinates if he felt that his supervisor was treating them unfairly. He took great interest in those who worked for him and tried to help them develop their professional skills. When someone was unable to carry out a task, he did not take it away from him and give it to someone else, but rather coached and taught the person until he learned how to do it. He also helped the people who worked for him to prepare for the competitive exams on which most promotions depended.

He was equally open to employees of all political persuasions. One of his workers had been purged as a “Red,” but subsequently cleared. Most people avoided him, perhaps out of fear that in the highly charged atmosphere of Franco’s Spain they might themselves be considered suspect. Isidoro not only did not keep his distance from him but helped him find a second job where he could supplement his income. At his death, the people who reported to him signed a declaration saying that he “was known as a saint because of his extreme goodness.”

Starting in July 1939, Isidoro’s schedule called for him to work from seven in the morning to two in the afternoon. He had to rise very early by Spanish standards in order to be able to do his morning meditation and hear Mass before going to work. On the other hand, this schedule made it possible for him to dedicate the afternoon and evening to his responsibilities as General Administrator of Opus Dei.

Among his first tasks was overseeing the installation of a new university residence in several rented apartments on Jenner street in Madrid. The task was complicated by the lack of money and shortages of almost everything in post-Civil War Madrid. Isidoro spent a great deal of time going from shop to shop looking for furniture, housewares, and even food for the residence.

For help in solving the many problems he faced as Opus Dei’s Administrator, Isidoro often turned to the Blessed Virgin. Shortly before his death, talking to a young man who had just joined Opus Dei he told him about the times when:

We didn’t have a house nor clothing nor anything at all; just love and faith in the most holy Virgin who, little by little helped us overcome the difficulties. Those of you who are younger have come across the Work already underway and even flourishing. All of this that you see is the fruit of the great love that our Lady has for us. We have to love her with our whole soul, with a love infinitely greater than all the loves of the earth. How well she has treated us!

Between his professional work and his duties as Administrator Isidoro was extremely busy, but he found time to accompany Escrivá and other members of the Work on trips to other cities where they could meet young men and explain Opus Dei to them. He also took advantage of every opportunity to get to know the young men who joined Opus Dei after the Civil War and to pass on to them its spirit. St. Josemaría told the members of the Work in the recently opened center in Valencia that he had asked Isidoro to visit them “so we could learn to do things right.” During his visit, Isidoro repaired various things in the house and taught them how to do the accounts and how to live poverty in very small things, for instance, using as scratch paper, pieces of paper that had already something written on one side. He urged them to correct even small mistakes in the accounts, not because a couple of pesetas were important but because the spirit of Opus Dei requires showing love of God by doing small things well. He was careful never to wound them and praised what they had done well, or at least their goodwill.

Despite being the oldest member of the Work, Isidoro tried not to stand out. He rarely talked about things he had done during the Civil War. He consulted del Portillo, the Secretary General of the Work, about many issues, even though del Portillo was younger and had joined Opus Dei after him.

Final Illness and Death

In the Fall of 1940, Isidoro moved to a newly opened center in Madrid. The house was large and handsome, but needed repairs. During the winter of 1940-41 the heat did not work. Isidoro suffered from the cold and from other health problems. Although already very thin, he lost weight and had little strength. He began to find going up the stairs exhausting. In July 1941, he was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma and given two years to live. Although he was in considerable pain and unable to sleep, for a year he was able to continue working and carrying on a normal life including fulfilling his duties as Administrator of Opus Dei and taking responsibility for furnishing a new center in Madrid.

Just before Christmas 1942, Isidoro made a retreat preached by Escriva. After a meditation on death, he remained in the oratory. Thinking that he was alone, he said softly, “Lord, I’m ready.” Shortly thereafter, he entered a clinic. Escrivá told him that he had days or at most a few months left to live. His immediate reaction was a look of repugnance, but he soon reacted and asked Escrivá what he wanted him to take care of from heaven and what he should pray for. In the clinic, he wanted only books that talk about God. When visitors came, he sometimes turned on the radio, but once they left, he turned it off. He had to force himself to eat, but he did so “thinking of the many needs of the Church.” His doctor told other patients about Isidoro, and concretely about “his attitude toward death, his courage in the face of pain, his remarkable patience and his constant smile.”

One doctor frequently told him that he was getting better. At first, Isidoro pretended to assent, but finally, he said, “I very much appreciate your good intentions, but there’s no point in trying to deceive me. I realize that for a long time now there’s been nothing you can do for me. I am in God’s hands and very content. … There can be no doubt that it is the Lord who gives me this peace and this joy. No doubt he is the one.”

Toward the very end of his life, he confided to another member of the Work:

Our obligation is to fulfill the duty of each moment. My only duty is to suffer. … I don’t have to worry about anything else. I suffer a great deal. It is remarkable how much you can suffer. At times, it seems you can’t suffer more, but the Lord gives greater strength. What a joy to think that one is useful. Suffering with supernatural spirit is how we have to move the Work forward. Pain purifies. The longer the trial, the better. In that way we will purify ourselves more.

Isidoro did not request special attention. The doctor in charge of the clinic says that he does not recall Isidoro ever calling for him to come. If a nurse was taking care of him and he heard a call bell ring he would say, “Why don’t you go see what they need? I can wait.” Toward the end of his life, the nurses found it impossible to understand what he was asking for. After bringing him several things that were not what he needed, they would say that they were sorry but could not understand him. He remained very calm and showed no sign of being upset.

Isidoro died on July 15, 1943.

Zorzano’s cause of Beatification was opened by the Archdiocese of Madrid. In 2015, Pope Francis approved a decree declaring that he had lived the virtues in a heroic manner.

This sketch of Father Joseph Múzquiz is from John Coverdale's book and podcast "Encounters: Finding God in All Walks of Life." Encounters presents profiles of people living Saint Josemaria's message of finding God in everyday life.

The profiles have been released as an audio podcast series, available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your podcasts. You can also purchase the entire book from Amazon or Scepter Publishers.